Beer, Dreams, and Divine Visions:

Did the Ancient Egyptians Unlock the Spirit World with DMT?"

In recent years, a fascinating theory has emerged suggesting that the ancient Egyptians may have known about and used N, N-Dimethyltryptamine (DMT), a powerful hallucinogenic compound, in their religious practices. Proponents of this idea draw connections between the myth of Osiris, the Egyptian Tree of Life (often associated with the acacia tree, a known source of DMT), and the transformative spiritual experiences reported in modern-day DMT users.[1] While this theory offers an alluring interpretation of Egyptian spirituality, it faces a significant challenge: the lack of direct evidence for using DMT in ancient Egypt. Instead, the historical and archaeological record suggests a different, more well-documented medium for connecting with the divine—ritual drunkenness, mainly through beer consumption, in temple practices.

This article will explore the speculative idea that ancient Egyptians might have used DMT, contrast it with the more substantiated practices of dream incubation through ritual intoxication, and examine how both methods represent different paths toward achieving spiritual communion.

DMT in the Context of Ancient Egyptian Religion: The Hypothesis

The hypothesis that ancient Egyptians used DMT draws on several symbolic and mythological interpretations. In Egyptian mythology, Osiris, the god of the dead and resurrection, is closely associated with the acacia tree. The acacia, widespread in Egypt, contains DMT in its leaves and bark. Some have proposed that ancient Egyptians may have extracted and consumed DMT in religious rituals to achieve altered states of consciousness, much like indigenous South American shamans do with ayahuasca, a brew containing DMT.

In this framework, the Osiris myth—centred on death, dismemberment, and resurrection—can be seen as an allegory for the transformative experiences often reported by DMT users, who describe encounters with otherworldly beings, the dissolution of the ego, and contact with a transcendent realm. The ancient Egyptians' belief in an afterlife and their focus on spiritual resurrection align with the narratives of rebirth and revelation commonly associated with DMT. The phrase "as above, so below," found in Egyptian texts and echoed in Hermeticism, also resonates with the mystical insights reported by modern DMT users who feel they have glimpsed a more profound, universal truth.

However, while this theory is intriguing, it is speculative. There is no direct textual or archaeological evidence that the Egyptians extracted DMT from the acacia tree or used it in any form resembling a hallucinogen. Unlike in South American cultures, where clear historical and ethnographic evidence supports the use of DMT in shamanic practices, Egypt's religious texts, tomb inscriptions, and temple records offer no concrete indication that such substances were used in rituals or spiritual experiences.

Beer, Drunkenness, and Dream Incubation: A Well-Attested Practice

In contrast to the speculative theory of DMT use, the ancient Egyptians left abundant evidence of a well-established practice involving intoxication—ritual drunkenness, mainly through the consumption of beer. Beer played a central role in the ancient Egyptians' daily lives and religious practices, serving not only as a dietary staple but also as a potent spiritual tool in certain temple rituals. The practice of ritual drunkenness, particularly in the context of dream incubation, was a key method by which ancient Egyptians sought communion with the divine.

The Temple of Hathor at Dendera provides a famous example of how beer and drunkenness were integrated into religious practices. Hathor, a goddess associated with fertility, motherhood, and music, was also known as the "Mistress of Drunkenness." Each year, the "Feast of Drunkenness" was celebrated in her honour, during which participants would drink copious amounts of beer until they reached a state of intoxication. This ritual was believed to induce a divine state of altered consciousness, allowing individuals to communicate with the gods or receive prophetic dreams.

Temple of Hathor at Dendera

Similarly, the practice of "dream incubation," where individuals would sleep in temples hoping to receive divine messages through dreams, was also enhanced through intoxicating substances like beer. Beer, as a psychoactive substance, was thought to relax the mind and open it to the influence of the divine. Participants in these rituals would drink until they fell into a stupor when the gods were believed to visit them and impart wisdom or healing through dreams.

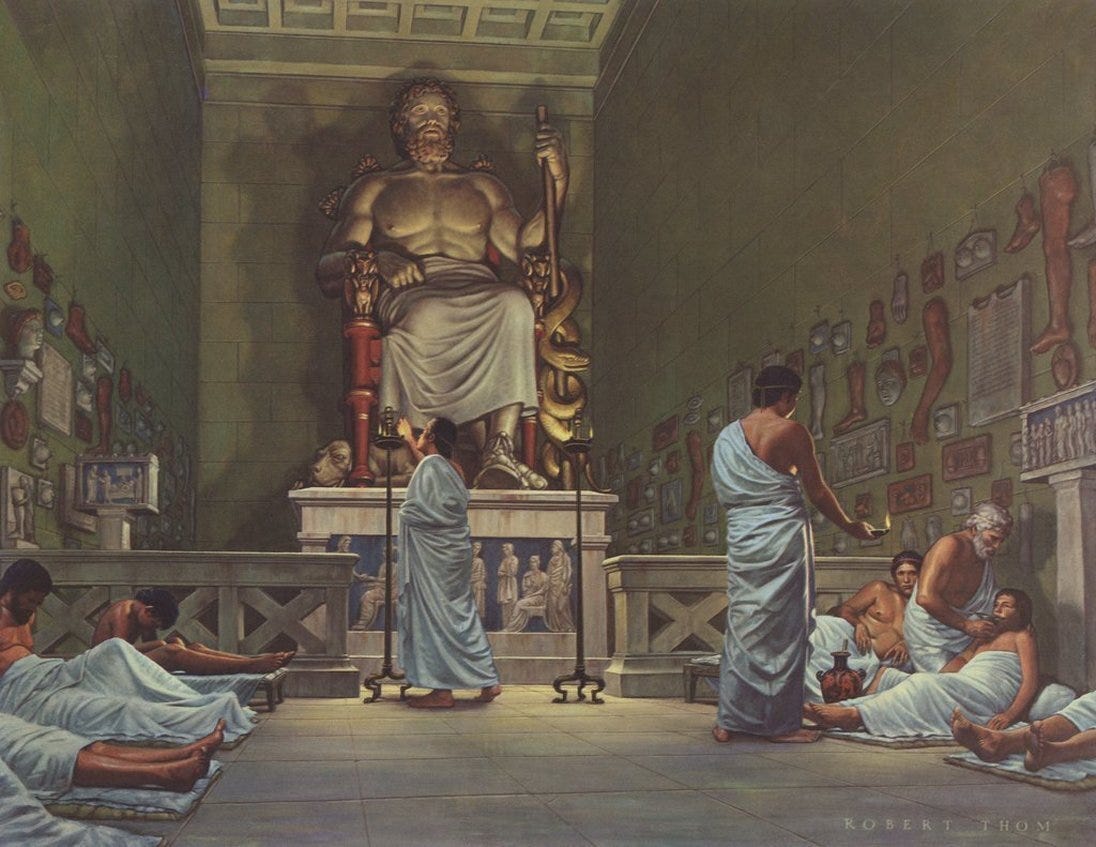

These practices are well-documented in Egyptian texts and temple records. Dream interpretations, for instance, were a common feature of Egyptian religious life. Temples like those dedicated to Imhotep, the deified architect and healer, were places where individuals sought divine intervention through dreams, often aided by rituals that included offerings, chanting, and intoxicants like beer.

Ritual Intoxication vs. Hallucinogenic Experiences

While both ritual drunkenness and the speculative use of DMT can be seen as methods of altering consciousness to commune with the divine, the nature and cultural contexts of these experiences differ significantly.

First, the medium itself sets the two practices apart. Beer, a mild intoxicant, was readily available and deeply ingrained in Egyptian daily life. It was accessible to all classes and used in mundane and sacred contexts. Its effects—intoxication, relaxation, and lowering inhibitions—were likely seen as facilitating a spiritual openness to the gods, but in a way considered familiar and socially acceptable.

Shabti figures brewing beer.

DMT, on the other hand, is a powerful hallucinogen that induces profound visual and sensory distortions, often described as transporting users to alternate dimensions or realities. Given the substance's potent effects, if the Egyptians had used DMT, it would have likely been in a highly specialized, esoteric context. Unlike beer, which could be consumed in communal settings, DMT's effects would have made it a substance reserved for specific, controlled religious rituals, much like how ayahuasca is used in South American shamanic ceremonies today. However, the lack of evidence for such practices in Egypt suggests they did not pursue this path.

Second, the purposes of these practices differ. Ritual drunkenness, particularly in the context of dream incubation, was primarily about creating an open, receptive state of mind for divine messages, often related to personal healing or prophecy. The focus was on practical, tangible outcomes—communication with gods, healing, or resolving personal issues. In contrast, as understood in modern contexts, DMT use often results in more abstract, mystical insights about the nature of reality, consciousness, and the cosmos. The Egyptians were deeply concerned with the afterlife and the maintenance of cosmic order (ma'at), and while they pursued spiritual knowledge, their religious practices were often highly practical, focused on ensuring safe passage to the afterlife or maintaining divine favour.

Conclusion: Two Paths to the Divine

While the idea that the ancient Egyptians may have used DMT to achieve altered states of consciousness is an intriguing and imaginative hypothesis, the lack of direct evidence makes it difficult to support. What we do know, however, is that the Egyptians practised ritual intoxication through beer consumption as a well-documented method for connecting with the divine. Ritual drunkenness and dream incubation offered a communal, accessible way for the Egyptians to engage with their gods, while the speculative DMT use—if it existed—would have represented a more esoteric and less accessible practice. Ultimately, both paths highlight the Egyptians' profound desire to connect with the divine, whether through the tangible medium of beer or the speculative realm of hallucinogens.

[1] https://grahamhancock.com/vooghtr3/