When we think of ancient Egypt, images of grand pyramids, mysterious tombs, and elaborate burial rites, we assume the ancient Egyptians had a massively successful state religion, but many Egyptologists don’t see it that way.

For example, in "The Search for God in Ancient Egypt" (2001), the eminent and much admired Jan Assmann describes ancient Egyptian religious life as less about a unified theological system and more about localised cultic practices. He presents the idea that Egyptian religion was inherently pluralistic, allowing for many deities and forms of worship without any central orthodoxy. Integrating different cults under the Egyptian state was more a matter of political organisation than an expression of spiritual unity and led to the coexistence of numerous local gods like Amun in Thebes, Ptah in Memphis, and Horus in Edfu. Another prominent example of this point of view can be found in David Frankfurter's "Religion in Roman Egypt: Assimilation and Resistance" (1998), which focused on the continuity and transformation of local cults within Egyptian society, especially during the Greco-Roman period. Frankforter concludes that Egypt’s "religion" was a patchwork of local traditions, each with its own deity and ritual practices supporting the view that Egyptian spiritual life was not centralised but highly regional, with each community having unique relationships with its local gods.

Those espousing the opposing view include the eminent and admired Erik Hornung, who, in "Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many" (1982), argued for the presence of a complex but unified theological framework in ancient Egypt. He suggests that while ancient Egyptian religion was polytheistic, it possessed an underlying sense of unity. This is evident in the concept of Amun as the hidden, universal god and the tendency to merge various gods into composite deities or view them as different aspects of a single divine essence.

American scholar James P. Allen provides a detailed examination of the religious texts from the Old Kingdom period, emphasising the consistency and ritual coherence of these texts as evidence of a structured belief system. Allen’s interpretation suggests that the belief in Ma'at and the pharaoh’s divine role functioned as a unifying religious framework, effectively binding the disparate cults into a cohesive religious system in "The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts" (2005).

Cult or Religion: What’s the Difference?

The word “religion” might seem obvious to us today, but for ancient Egyptians, there was no such word in their language. However, just because a term didn’t exist doesn’t mean the concept didn’t. The lack of an official word for religion has led some Egyptologists to argue they had no formal religion as we would understand it, but instead, they had a deeply ingrained system of beliefs that permeated every aspect of their lives. Their “religion” was what Egyptologists call a ‘cult’ and was more about maintaining harmony in the universe—through rituals, offerings, and daily devotion to the gods than our modern conception of a religion which seeks to provide answers to fundamental questions about existence, the meaning of life, the nature of good and evil, and what happens after death.

What Is a Cult?

In Egyptology, a “cult” refers to the daily worship of a deity, particularly through the care of a god’s image or statue. Egyptian temples weren’t just places of prayer; they were the homes of the gods. Here, priests tended to the gods’ needs—cleaning, dressing, and feeding their statues in elaborate rituals.

Cults played a significant role in religious life but differed from the organised religions we recognise today. A cult in ancient Egypt referred explicitly to the daily practices and rituals surrounding the worship of a deity’s image, which was housed in a temple. These cults focused on the physical care of the god’s statue, including feeding, clothing, and offering prayers performed by priests on behalf of the community or the Pharaoh. The belief was that these rituals kept the gods active in human affairs and maintained cosmic order. However, these cults were often localised, centring on specific gods worshipped in particular regions, with no unifying religious doctrine across the entire nation.

The pharaoh was theoretically responsible for these ceremonies as the intermediary between the gods and the people. In practice, however, priests usually filled this role. The gods themselves were believed to descend from the heavens to inhabit their statues, becoming physically present in the temple.

The Daily Routine of the Gods

Every day began with the shrine's opening. Priests would greet the god believed to inhabit the statue with prayers and hymns, offering food, water, and incense. The statues were bathed, dressed in fresh linen, and offered a symbolic meal of bread and cakes. The gods were “put to bed,” and their statues returned to their shrines to rest until the next day.

The enthroned god Atum is being offered bread as a gift by the pharaoh.

There is a belief among Egyptologists that the cults were local, each god had its geographical domain, and that the Egyptians believed rituals were essential for maintaining order in the cosmos, ensuring the sun would rise, the Nile would flood, and life would remain balanced. Some Egyptologists call this a relationship based on material transactions, not one based on complex beliefs like Catholicism; thus, ancient Egyptian cults can be seen as more fragmented and ritualistic, whereas modern religions offer a more cohesive and philosophical approach to spirituality and the meaning of life.

To assess whether ancient Egypt's spiritual system qualifies as a "religion," it's helpful to refer to commonly accepted criteria used by scholars of comparative religion. Below is a set of criteria typically used to define what constitutes a "religion":

1. Belief in the Supernatural or Divine

A vital feature of a religion is the belief in supernatural entities or forces. In ancient Egypt, this is represented by their pantheon of gods, such as Ra, Isis, Osiris, and Amun. These deities were not just mythological figures but were considered to have direct influence over the physical and spiritual realms, reflecting a structured supernatural worldview.

2. Rituals and Ceremonies

Religions generally have a set of prescribed rituals and ceremonies, often designed to appease or communicate with the divine. In ancient Egypt, priests and pharaohs performed elaborate rituals in temples, such as the daily offering rituals to the gods, the "Opening of the Mouth" ceremony for the dead, and the New Year’s festival celebrating the inundation of the Nile. These rituals suggest an organised system with designated participants and prescribed actions, meeting the criterion for ritualistic practice. Moreover, the so-called ‘Civil Calendar’ of 365 days in the Old Kingdom shows a series of nationally set days of feasting and religious activity, such as the Wag Festival, which took place during the first month of the ancient Egyptian calendar, specifically during the month of Thoth, corresponding roughly to late August or early September in our modern calendar. It often coincided with the annual flooding of the Nile (the inundation), which was seen as a time of regeneration and renewal, aligning symbolically with themes of rebirth and the afterlife.

3. Moral or Ethical Framework

Most religions provide a moral or ethical framework that guides behaviour. In ancient Egypt, this is embodied in the concept of Ma'at, which represented truth, balance, order, and justice. Ma'at was a divine principle crucial to maintaining cosmic order, and individuals and rulers were expected to live by its tenets. The adherence to Ma'at was an ethical foundation for Egyptian society, reinforcing the idea of a structured moral component akin to those found in other religions.

Moral and Ethical Guidelines or Rules

People were expected to adhere to ethical guidelines or rules given by the divine. The 42 Statements of Innocence, also known as the Negative Confessions or Declarations of Innocence, come from the Egyptian Book of the Dead. The deceased recited them before the gods, proving they had led a just and honourable life.

The Ten Commandments are ethical guidelines God gave to Moses on Mount Sinai, foundational to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Here’s a comparison of the similarities and differences between the Egyptian and Hebrew ethical rules:

Both serve as moral codes, guiding individuals toward righteous behaviour. For example, the Egyptian statement "I have not killed" parallels the Sixth Commandment, "Thou shalt not kill." Statements like "I have not stolen" and "I have not told lies" are similar to "Thou shalt not steal" and "Thou shalt not bear false witness." Both emphasise respect for human relationships. The Ten Commandments focus on honouring parents ("Honor thy father and mother"), while the Negative Confessions contain statements like "I have not disrespected my parents." Furthermore, both address fidelity in relationships. The Egyptian statement "I have not committed adultery" aligns with the Seventh Commandment, "Thou shalt not commit adultery."

The differences include their scope and format. For example, the Ten Commandments are concise, focusing on crucial directives in a list of ten, while the 42 Statements of Innocence are much more expansive and detailed, covering many more aspects of daily life. Also, the Ten Commandments begin with directives about loyalty to a single god ("Thou shalt have no other gods before me"), reflecting the monotheism of the Jews, which contrasts with ancient Egyptian polytheism. Of course, the Ten Commandments stress the prohibition of idolatry, such as "Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image," whereas the Egyptian Negative Confessions do not contain such specific prohibitions against idol worship, as their belief system involved worshipping many gods through images and statues.

While the Ten Commandments focus on the individual, the 42 Statements also emphasise a strong ethical responsibility to the community. For example, I have not polluted the water" and "I have not stopped the flow of water," reflecting a broader concern for societal and environmental ethics. The Egyptian statements also address specific ethical behaviours, such as "I have not been angry without cause" and "I have not eavesdropped," focusing more on personal behaviour and manners rather than strictly moral transgressions.

The Egyptian Statements are centred around the concept of Ma'at—truth, balance, and justice. This is broader than the individual moral laws of the Ten Commandments. For instance, "I have not diminished the offerings to the gods" shows the connection to maintaining cosmic and social order, whereas the Ten Commandments focus more on human-to-human and human-to-God relationships.

So, the 42 Statements of Innocence and the Ten Commandments aim to guide people in living morally upright lives, but they reflect different religious contexts and cultural values. The Ten Commandments are concise, direct, and rooted in monotheism, while the Negative Confessions are more extensive, reflecting a polytheistic society focusing on personal, social, and environmental justice. Both guidelines share common moral tenets, such as prohibitions against murder, theft, and dishonesty, but diverge significantly in their approach and focus on spirituality and everyday conduct.

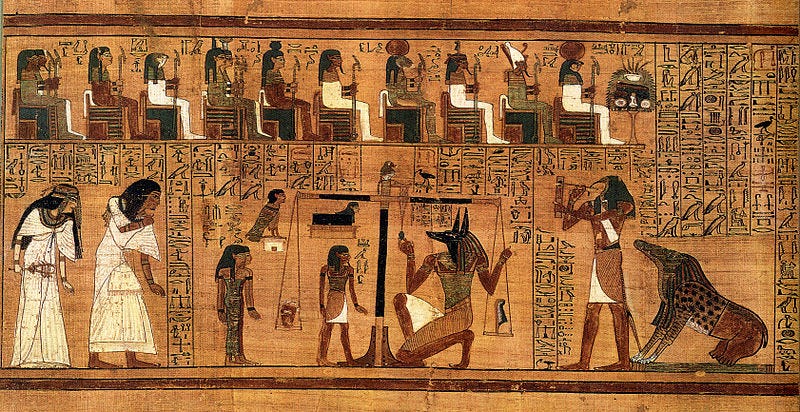

The Weighing of the Heart ceremony in the Hall of Two Truths: Book of the Dead

4. Sacred Texts or Mythologies

Religions often have sacred texts or mythological narratives that convey their core beliefs and values. In the case of ancient Egypt, the Old Kingdom Pyramid Texts, The Middle Kingdom Coffin Texts, and the New Kingdom Book of the Dead served as sacred writings that offered guidance for both the living and the deceased on achieving immortality and maintaining cosmic harmony. These texts played a critical role in defining the belief system, documenting rituals, and outlining the mythologies of their gods, thus meeting the criterion for having sacred narratives.

In the context of ancient Egyptian religious and philosophical literature, Wisdom Texts played a crucial role in conveying ethical guidelines, social conduct, and reflections on morality, justice, and human behaviour. These texts are also significant because some scholars argue that they influenced the Book of Proverbs and other wisdom literature in the Hebrew Old Testament. Below are three prominent examples of Egyptian wisdom texts:

The Instruction of Merikare: Middle Kingdom, approximately 2100–2000 BC

The Instruction of Merikare is attributed to an unnamed king advising his successor, Merikare, on governance and the duties of a ruler. The text provides political, social, and moral advice, stressing the importance of Ma'at (the principle of truth, balance, and cosmic order) in leadership. It emphasises the need for rulers to be just, benevolent, and mindful of their people’s needs. There are also instructions regarding the treatment of foreign people, the importance of wisdom, and the necessity of ethical conduct in governance. It is considered a significant contributor to the development of later Jewish thought. The themes of righteous rulership, justice, and leaders' responsibilities echo similar ideas found in the Bible.

The Instruction of Ptahhotep: Middle to Late Old Kingdom, approximately 24th century BC

The Instruction of Ptahhotep is one of ancient Egypt's oldest known wisdom texts. It is a collection of maxims and moral teachings attributed to Ptahhotep, a vizier serving during the reign of King Izezi of the Fifth Dynasty. The teachings focus on practical advice for a successful life, such as humility, respect for authority, social justice, and moderation in speech. This text embodies a pragmatic approach to morality and societal conduct and emphasizes virtues such as fairness, honesty, and self-control. Several themes in the Instruction of Ptahhotep resemble those found in the Book of Proverbs. For instance, it emphasizes avoiding anger, being humble, and being cautious with words—values also prevalent in Proverbs, suggesting a possible influence or shared cultural context.

The Instruction of Amenemope: Late New Kingdom, approximately 1300–1075 BC

The Instruction of Amenemope, a high-ranking official, is a collection of ethical maxims to guide individuals toward a life of integrity, contentment, and inner peace. It advises avoiding greed, treating others with kindness, and accepting one's lot in life. The instructions often emphasise moderation, honesty, patience, and respect for others and warn against dishonesty and exploitation. This text is particularly noteworthy because many scholars believe that parts of the Hebrew Book of Proverbs, specifically chapters 22:17–24:22, directly parallel Amenemope’s advice. For example, both texts share similar language and themes. The similarities are striking enough to suggest The Instruction of Amenemope influenced the composition of the biblical proverbs, particularly in their focus on humility and divine order.

5. Organised Clergy or Religious Specialists

Middle Kingdom block statue of a priest of Amun, Thebes.

Another criterion of religion is the presence of an organized clergy or specialised religious class. In ancient Egypt, a structured priesthood conducted ceremonies, maintained temples and interpreted the gods' will. High priests held significant authority, and their duties were often state-sponsored, suggesting a systematic religious institution akin to a clergy.

The organisation of the ancient Egyptian clergy evolved considerably over the millennia, adapting to political, cultural, and economic changes from the Old Kingdom through the Roman period. Below is a brief outline of the structure and evolution of the Egyptian priesthood during these periods.

Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2181 BC)

In the Old Kingdom, temples were primarily dedicated to the cult of the pharaoh as a divine figure, and the gods were closely associated with kingship, such as Ra at Heliopolis, where the High Priest was known as the "Great One of the Observers" or "wr-mꜣw”. The temples also employed a variety of lesser priests, including wab priests responsible for the purification of temple areas and conducting minor rituals. Most priests served on a rotational basis, often for a month.

Middle Kingdom (c. 2055–1650 BC)

During the Middle Kingdom, the country's religious focus moved to Thebes and the worship of Amun. Temples owned vast estates, which required administrative officials, often priests, to manage resources and ensure the sustenance of temple activities. The clergy expanded as the temples gained incredible wealth and influence. The High Priest was entitled "High Priest of Amun". Specialised roles expanded, including the creation of lector priests (ḥry-ḥb), who recited religious texts, and sem priests, who were involved in funerary rites.

New Kingdom (c. 1550–1070 BC)

In the 18th Dynasty, the cult of Amun at Karnak grew immensely powerful. The high priests of Amun held significant political and economic influence, rivalling that of the pharaoh. The High Priest of Amun became a key power broker controlling large tracts of land and a massive workforce, giving them a substantial role in state affairs, especially during the reigns of Ramesses II and Hatshepsut. Temples began to serve as centres for oracle rituals, further increasing their influence. The New Kingdom also saw the revolutionary introduction of the role of the God’s Wife of Amun, a position often held by royal women.

Late Period (c. 712–332 BC)

The Egyptian priesthood became even more integral to the state's governance. The division of power in the country sometimes led to high priests, such as those of Amun, effectively becoming rulers in their regions, particularly in Thebes.

After the conquest of Alexander the Great, the priesthood adapted by integrating Greek elements into their traditional religious rituals. The Greek rulers supported temples to legitimise their authority, and the priests acted as intermediaries between the new rulers and the native population.

Ptolemaic and Roman Period (c. 332 BC – 395 CE)

Under the Ptolemies, the organisation of the Egyptian clergy saw increased Hellenisation. Many deities were syncretised with Greek gods, like Serapis, a deity combining elements of Osiris and the Greek god Zeus. The priesthood continued to serve in administrative roles, including managing temple estates, which remained the key centres of economic power and cultural preservation.

With the Roman conquest in 30 BCE, the independence of the Egyptian priesthood began to decline. The Romans did not support the temples in the same way as the Ptolemies, and the role of the clergy was increasingly limited to religious observance. The Roman state tightly controlled the wealth of the temples, and the gradual spread of Christianity contributed to the decline of traditional Egyptian religion.

6. Community of Believers

The ubiquity and sheer scale of religious monuments, temples, mortuary complexes, and artefacts in Egypt reveal a culture deeply entwined with spiritual practices. Egypt’s massive construction projects involved many of the population in building, maintaining, and conducting rituals within these sacred spaces.

The number of tombs and funerary items points to an all-encompassing belief in an afterlife that required continuous, organised effort at every level of society, from the pharaoh and high priests down to the ordinary workers who built these structures and those who ensured the spiritual needs of the deceased were met.

Unlike Mesopotamia, Greece, or Rome, where monumental religious constructions were prominent but more localised or civic in nature, Egyptian monuments were pervasive, reflecting a religious consciousness embedded into every part of daily life. The pyramids, temples, statues, and countless other religious artefacts found across the Nile Valley suggest that a massive community of believers, unified in their devotion to the gods and the afterlife, shaped Egypt for over three millennia.

7. Doctrine of the Afterlife

The belief in an afterlife is a crucial element in the definition of many religions, providing a framework for understanding human existence beyond death. In ancient Egypt, belief in the afterlife formed a core tenet that defined their religious identity, giving purpose and direction to rituals, social practices, and monumental construction projects. This belief infused Egyptian life from the personal to the state level, profoundly influencing morality, ethics, and governance.

In a broader religious context, belief in the afterlife often serves several key functions. It explains what happens after death, providing a sense of continuity beyond the physical life, thereby addressing humanity's existential concerns. It also provides a moral incentive, as seen in the concept of Ma'at in Egyptian religion, where maintaining cosmic order in life was crucial for a favourable journey through the afterlife. This serves as a spiritual motivator, guiding ethical behaviour through promises of rewards or consequences after death.

In ancient Egypt, elaborate burial practices, the construction of pyramids, and the inclusion of texts like the Book of the Dead emphasised preparing the deceased for an eternal journey, showcasing the prominence of afterlife belief. Such comprehensive preparation reflects a profoundly ingrained collective religious consciousness, defining their community identity. The importance placed on achieving a positive afterlife aligns with how religions create meaning, bind societies together through shared rites, and provide comfort and structure to followers facing the unknown of death.

Coffin lid of priest Heryshef Nedjemankh.

Cult or Religion: Why does it matter?

Based on these criteria, I am convinced ancient Egypt's belief system qualifies as a "religion" rather than just a collection of regional cults. The distinction between viewing ancient Egypt as having a cohesive religion rather than a collection of unconnected local or regional cults is fundamental in understanding the nature of its culture, society, and political structure. These two perspectives offer different insights into how ancient Egyptians viewed the world, organised their society, and constructed their enduring legacy. Each interpretation has profound implications for understanding ancient Egypt's cultural unity, governance, social cohesion, and the transmission of values.

If we consider ancient Egypt to have a cohesive religion, this implies a significant level of cultural unity across the entirety of the Nile Valley. Religion would serve as a unifying force, connecting diverse regions and peoples under a shared set of beliefs, rituals, and values. This unified religious framework helped to maintain social harmony and a collective Egyptian identity. The idea of Ma'at—representing cosmic order, truth, and justice—was central to Egyptian thought and was upheld by the pharaoh and every individual as part of their religious duty. Such a belief system that permeates all layers of society underscores a unified worldview rather than disparate traditions.

In contrast, seeing Egypt as consisting of local cults—each primarily concerned with their regional deity—suggests a more fragmented social structure where religious practice was largely region-specific, with no overarching unity beyond political necessity. For instance, the cults of Amun at Thebes, Ra at Heliopolis, and Ptah at Memphis were geographically distinct, each with their rituals, festivals, and societal significance. Suppose we interpret Egyptian spirituality through the lens of regional cults. In that case, it implies that each community primarily identified with its local deity, potentially leading to diverse and even competing spiritual practices rather than a cohesive national identity.

Believing that Egypt had a structured religion inherently enhances the role of the pharaoh as not just a political figure but a divine intermediary whose legitimacy was grounded in faith. The pharaoh was seen as the living embodiment of the gods on earth, the essential link between the sacred and the mortal realms. This interpretation positions the pharaoh as a central figure whose religious authority unified the kingdom. The vast resources dedicated to building pyramids, mortuary temples, and the celebration of state-sponsored festivals such as the Sed Festival were meant to reinforce the ruler's divine status and uphold the state's religious order.

Conversely, viewing ancient Egyptian spirituality as a series of regional cults downplays the central religious authority of the pharaoh. In this scenario, the pharaoh’s influence would be seen more as a political necessity to ensure the allegiance of various regions rather than an embodiment of divine order. For example, the cult of Amun gaining political influence during the New Kingdom can be seen as reflecting the shifting power dynamics between centralized royal authority and regional religious power. This interpretation implies that the power of individual cults could rival that of the state, suggesting a more complex and potentially unstable political landscape where regional loyalties might overshadow national unity.

If Egypt had a unified religion, the temples functioned as more than centres of local worship; they were integral to the state's economic, administrative, and social systems. Temples such as Karnak, dedicated to Amun, or the temple complex at Dendera, dedicated to Hathor, acted as focal points for religious and economic activity. They were repositories of wealth, centres of learning, and places where the community gathered, thereby integrating the spiritual with the social and economic life of the country. The interconnected network of temples, sustained through offerings and state sponsorship, reflects a religious system that transcended local interests and provided a shared foundation for the society.

If ancient Egypt is seen as a series of disconnected local cults, each temple primarily served its local population, reinforcing regional identity rather than a collective Egyptian culture. Each community’s devotion to its local deity—whether Ptah in Memphis or Sobek in Faiyum—would indicate that temples served more as independent religious units, loosely connected by political rule rather than as nodes in a unified religious network. The focus would be more on regional autonomy, with local priesthoods exercising considerable power within their domains, suggesting that social cohesion was maintained more through pragmatic alliances than a shared spiritual framework.

Viewing Egypt as having a cohesive religion implies a standardised set of beliefs and rituals propagated throughout the kingdom. Texts such as the Book of the Dead, the Coffin Texts, and the Pyramid Texts were not just regionally important but were widespread, offering guidance to all Egyptians on how to navigate the afterlife, regardless of where they lived. This standardization implies a shared spiritual journey and a unified set of values, focusing on the maintenance of Ma'at and the trip to the afterlife. It highlights the importance of collective participation in state rituals and the belief that the prosperity of Egypt was linked to maintaining cosmic order through these shared practices.

In contrast, if we interpret Egyptian spirituality as a set of regional cults, it suggests a more localized, varied set of beliefs where each community had its version of religious myths, rituals, and possibly different conceptions of the afterlife. This could mean that values and religious practices varied significantly from one part of Egypt to another, with no singular religious narrative binding them all together. It would indicate a more pluralistic spiritual environment where different traditions coexisted without the overarching theological unity that characterizes what we traditionally define as "religion."

The difference between seeing Egypt as having a unified religion versus a series of unconnected local cults is critical for understanding the nature of its cultural and political cohesion. A unified religion implies a cohesive national identity, centralised authority under the divine pharaoh, and shared values that permeated all levels of society. It paints a picture of Egypt as a nation united under a common spiritual purpose, with temples and rituals as symbols of religious devotion and political unity.

On the other hand, viewing Egyptian spirituality as local cults emphasises regional diversity, localised centres of power, and a more fragmented spiritual landscape, with religious practices that were varied and possibly even competitive. This perspective underscores the importance of regional identities and the role of local priesthoods in shaping community life.

Both interpretations offer valuable insights, but the notion of a unified religion highlights Egypt's ability to build one of the most enduring and influential cultures in human history. This culture is characterised by its immense monumental achievements, centralised power, and profoundly interconnected belief system.