Keats, Blue, and the Lady of the Sixteen

What's the Connection between the English poet John Keats, the colour blue and an ancient Egyptian goddess?

Readers in the UK who are fans of Radio Four’s RBQ (Round Britain Quiz) will be familiar with this challenging cryptic question. The panel game, which is one of the BBC’s longest-running quiz shows, tests the contestants’ knowledge and lateral thinking ability to make the connections between seemingly unrelated topics. Fortunately, you don’t have to work anything out - all the answers are here. I hope you enjoy finding out what the connections are and who the mysterious ‘Lady of the Sixteen’ was.

Sonnet on Blue

“Blue! ‘Tis the life of heaven,–the domain

Of Cynthia[1],–the wide palace of the sun,–

The tent of Hesperus[2] and all his train,–

The bosomer of clouds, gold, grey and dun.

Blue! ‘Tis the life of waters–ocean

And all its vassal streams: pools numberless

May rage, and foam, and fret, but never can

Subside if not to dark-blue nativeness.

Blue! gentle cousin of the forest green,

Married to green in all the sweetest flowers,

Forget-me-not,–the blue-bell,–and, that queen

Of secrecy, the violet: what strange powers

Hast thou, as a mere shadow! But how great,

When in an Eye thou art alive with fate!” John Keats

This little-known sonnet by John Keats is an unadulterated celebration of blue. It’s ecstatic and joyful and gives us some insights into how the ancient Egyptians thought about the colour (Egyptian blue), which was ubiquitously used in art, jewellery and pottery, often mimicking more expensive turquoise.

The poem’s inspiration had nothing to do with the sky. Instead, its genesis was a debate about which eye colour was the most attractive. Keat’s poet friend, J.H. Reynolds, declared that “dark eyes are dearer far / Than orbs that mock the hyacinthine-bell.” Keats, however, sidestepped the challenge and transcended it in a flash of brilliance, creating a poem that is a montage of rich, movielike scenes that move from sky to sea to forest in rapid succession until he finally addresses the colour of the blue eye which is ‘great’ or marvellous when ‘alive with fate’.

In the poem, Keats takes us to the “wide palace of the sun,” which the ancient Egyptians would have seen as the endless expanse of the waters of the primordial goddess Nun, the origin of everything that would ever exist and the source of the great flood that brought life and prosperity to everything it touched.

To the ancient Egyptians, the sky was the domain of all the gods, but of course, it was dominated by two, the moon and the sun, who were thought to sail in boats across its celestial waters. However, there was one enormous difference between the Greek and the Egyptian gods of the moon; the Greek god was female, and the Egyptian was always male (Osiris, Thoth, Ay, and Knoshu). The evening star, Venus, was also male for the Egyptians in the form of Horus. The tent of love for the Egyptians appeared with the Sirius, the Dog Star in the form of Sopdet or Isis, whose appearance heralded the arrival of the flood and the lazy ‘dog days’ of summer.

Then, Keats slips effortlessly into describing the vast ocean with phrases like “pools numberless” and the powerful alliteration of “rage and foam and fret.” The poem courses like a river through nature, spilling over its edges. The rage and fret of the flood would have been all too familiar to the ancient Egyptians. The Nile flooded almost every year for millennia without number until 1964, when the completion of the Great Aswan Dam created a permanent and impenetrable barrier across the river. Before the dam existed, a boundless torrent of water made its way north to the Mediterranean Sea from the heart of Africa every year. It would roar through the Aswan cataracts in July in a rage of white foam and then woosh down into the valley, scouring the land and covering it for the hottest summer months. As the flood water receded, it left hundreds, if not thousands, of pools and puddles that soon became home to a vast multitude of frogs who made them their nurseries. Soon, these pools were alive with an abundance of life. The numbers were so great. The ancient Egyptian symbol for 100,000 was a tadpole.

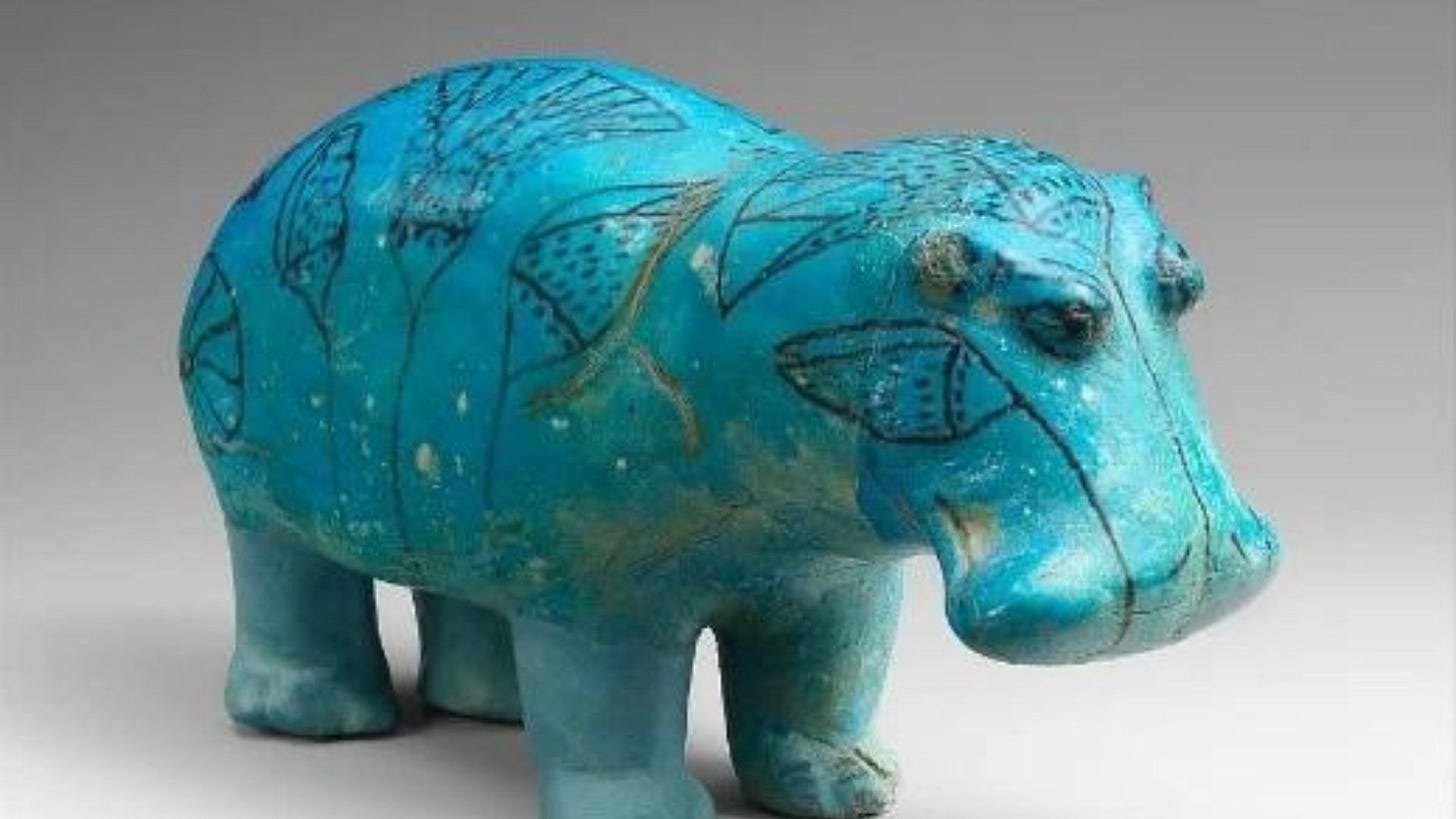

Keats then takes us to the woods, where blue becomes “the gentle cousin of the forest green.” Here, blue has subtler magic, enhancing the colours of flowers such as forget-me-nots, bluebells, violets, all woodland plants and symbols of everlasting love. For the Egyptians, the flowers that followed the flood were the lotus and papyrus, the blooms associated with regeneration and eternity. The blue-green colour of the river was the colour of life and rebirth in the afterlife and was worn in the form of turquoise or blue natron jewellery.

Turquoise was held in exceptionally high regard by ancient Egyptians because it seemed to them like a magical form of solid water. Known as mefkhat, it was therefore revered not only for its beauty but also for its magical power. Vivid green-blue turquoise stone represented life, fertility, and divine protection. The mines were in the Sinai Peninsula, known as the “Land of the Gods”, and protected by the goddess Hathor, who, amongst other epithets, was known as the “Mistress of Turquoise” and ‘The Lady of the Sixteen.’

The Greek historian Herodotus, who wrote about the annual flood in the 4th century BC, referred to the work of the pharaoh Sesostris III, who allocated an equal share of land to all his subjects in return for an equal payment of rent or tax. Senworset III or Sesostris III was the 5th pharaoh of Dynasty XII of the Middle Kingdom and ruled from 1878 to 1839 BC, during a time of great power and prosperity in Egypt. Further on, Herodotus tells us that the pharaoh offered a refund to any farmer whose land was damaged by a higher-than-average flood. That is a flood greater than 16-17 cubits (Book 2.109). Thus, Hathor, the goddess of all good things, was the ‘Lady of the Sixteen.’

The most popular amulets carved from turquoise were scarabs, ankhs, and hearts, all symbols associated with rebirth, protection, and life. The heart amulet, in particular, was believed to protect the deceased during the judgment of the soul, while the scarab amulet symbolized the sun’s daily rebirth and was often carved from turquoise as a potent symbol of eternal life.

For Keats, the blue eye of a woman was beautiful because it was full of life. To the ancient Egyptians, blue was beautiful because it was the colour of life - in this world and the next.

[1] In Greek mythology, Cynthia was an epithet for multiple goddesses, including Artemis, Selene, and the Roman Diana. Artemis was the virgin goddess of the hunt and the moon and the twin sister of Apollo. She was born on Mount Cynthus on Delos, where the epithet "Cynthia" originated. Selene was the Greek goddess of the moon, who was sometimes called "Cynthia" because of her close association with Artemis and Diana. Selene was the daughter of the Titans Hyperion and Theia. Diana was the Roman counterpart to Artemis. In Ancient Roman literature, "Cynthia" was the poet Propertius' name for love.

[2] The personification of the evening star, or the planet Venus in the evening.

Sources:

Andrews, Carol. Amulets of Ancient Egypt. University of Texas Press, 1994. Provides insights into the different types of amulets used in ancient Egypt, including those made from turquoise and their symbolic meanings in funerary contexts.

Baines, John, and Jaromir Malek. Atlas of Ancient Egypt. Facts on File, 1980. Offers a comprehensive overview of Egyptian geography, including the Sinai mines and the significance of turquoise in Egyptian culture.

Bourriau, Janine. Pharaohs and Mortals: Egyptian Art in the Middle Kingdom. Cambridge University Press, 1988. Examines Egyptian art, including turquoise artifacts, and discusses how materials like turquoise were incorporated into everyday life and the afterlife.

Friedman, Z. (2014). Nilometer. In: Selin, H. (eds) Encyclopaedia of the History of Science, Technology, and Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Springer, Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-3934-5_9644-2+

Hart, George. The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses. Routledge, 2005. Details the attributes and myths of Egyptian deities, including Hathor’s association with turquoise and its significance in Egyptian mythology.

Pinch, Geraldine. Magic in Ancient Egypt. University of Texas Press, 2006. Explores the magical and religious symbolism in ancient Egypt, including the protective qualities of turquoise and its use in amulets and funerary objects.

Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. Thames & Hudson, 2003. Provides an in-depth look at Egyptian deities, including Hathor and Ptah, and their connections to gemstones like turquoise.

Articles and Journals

Aston, Barbara G. "Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology: Precious Stones and Metals." Archaeometry, vol. 35, no. 1, 1993, pp. 89-101. Analyses materials used in ancient Egyptian artefacts, including turquoise, and the techniques employed in crafting them.

Nicholson, Paul T., and Ian Shaw, editors. Ancient Egyptian Materials and Technology. Cambridge University Press, 2000. This collection of essays provides an overview of the materials and technologies of ancient Egypt, with specific chapters dedicated to turquoise mining and the symbolic value of gemstones.

Reeves, Nicholas, and Richard H. Wilkinson. The Complete Valley of the Kings. Thames & Hudson, 1996. Discusses burial artefacts, including turquoise, found in tombs in the Valley of the Kings and their significance in the afterlife beliefs.

Websites

https://christopherjamespoet.wordpress.com/2021/10/01/blue-is-the-colour-on-a-lesser-known-sonnet-by-john-keats/ Provides an poet’s analysis of the Sonnet on Blue by Keats

Mark, Joshua J. "Turquoise in Ancient Egypt." World History Encyclopedia, 2021, www.worldhistory.org/turquoise. An online article that explores the origins, significance, and religious associations of turquoise in ancient Egyptian society.

"Hathor, Goddess of Love, Beauty, and Turquoise." Egyptian Museum Cairo, www.egyptianmuseumcairo.com/hathor. Provides details on Hathor’s role as the “Mistress of Turquoise” and her significance in Egyptian religion and myth.

"Mining Turquoise in the Sinai Peninsula: The Sacred Mines." Ancient Egypt Online, www.ancientegyptonline.co.uk/turquoisemining. Discusses the turquoise mining sites in Sinai and their religious significance, along with the god Ptah’s role in mining and craftsmanship.