Pharaoh, Pharaoh, How Does Your Garden Grow?

Magical plants in magical numbers

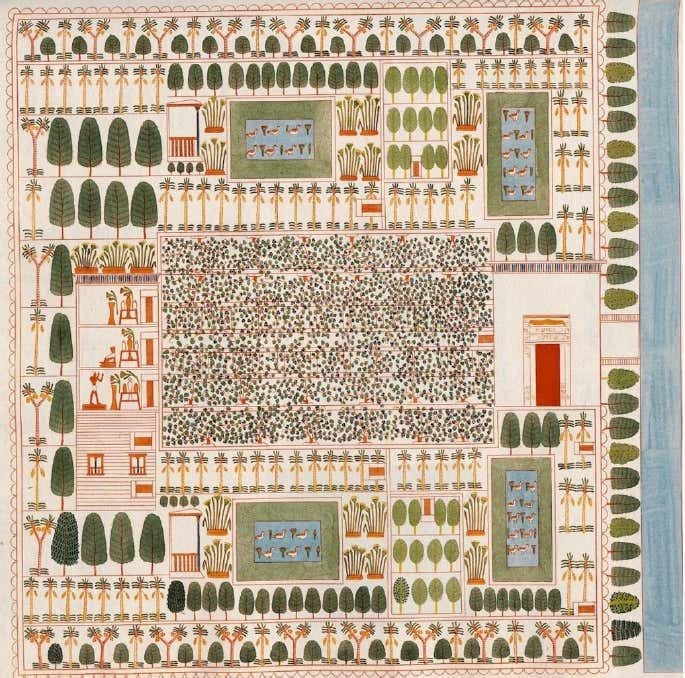

The beautiful illustration above shows a garden laid out in typical ancient Egyptian style. The strange but charming perspective is called ‘aspective’. It is the opposite of our modern Western view called ‘perspective’. The ancient Egyptian artist aimed to show all the essential details of a thing or person from a universal, not a personal viewpoint.

The image of the pond is halcyon. The animals, fish, and trees represent the peace and tranquillity of the ideal afterlife. The colours are tranquil to illustrate the peace and comfort of life in the Hereafter. Heaven was not perceived as a garden, but gardens were thought of as heavenly. The pond was a key component of most gardens because not only was it peaceful and beautiful, it represented the regenerative primordial waters of the goddess Nun and the primordial waters at the beginning of time.

The fish are most likely Tilapia, a freshwater fish associated with Hathor and used as a symbol of rebirth, resurrection, fertility, growth, and regeneration. Tilapia fish were often buried in graves to help the deceased achieve eternal life. Tilapia amulets were often worn as personal charms for fertility and by the dead as aids to renewal and regeneration.

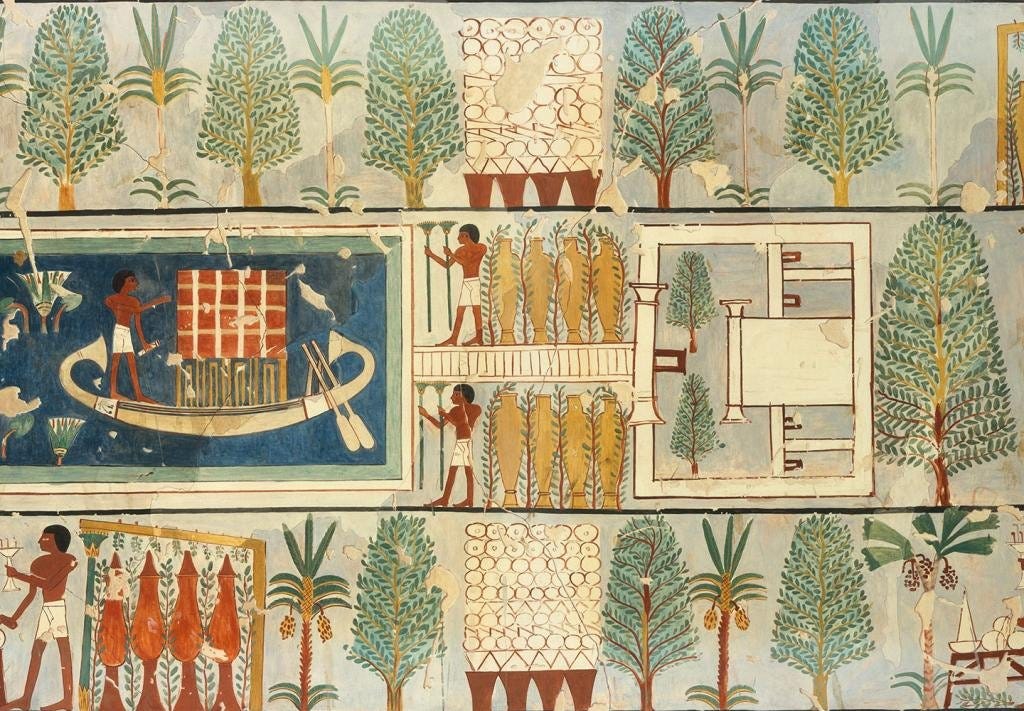

The wall painting is one of 11 acquired by the British Museum from the tomb chapel of a wealthy Egyptian official named Nebamun in the 1820s. The Tomb of Nebamun dates from Dynasty 18 and is located in the Theban Necropolis on the west bank of the Nile at Thebes (present-day Luxor) in Egypt. Nebamun (c. 1350 BCE) was a middle-ranking official scribe and grain counter at the temple complex in Thebes. His tomb was discovered in 1820 by a young Greek adventurer, Giovanni (“Yanni”) d’Athanasi, who acted as an agent for Henry Salt of the British Consul-General. D’Athanasi and his workmen hacked out the pieces he wanted with knives, saws, and crowbars, and Salt sold them to the British Museum in 1821. Some other fragments were sent to Berlin and possibly Cairo. D’Athanasi later died in poverty without ever revealing the tomb’s exact location.

In 2009, the British Museum opened a new gallery dedicated to displaying the restoration of eleven wall fragments from the tomb. They have been described as the most significant paintings from ancient Egypt to have survived and as one of the Museum’s greatest treasures. Objects dating from the same time and a 3-D animation of the tomb-chapel help to set the tomb-chapel in context and allow visitors to experience how the finished tomb would have looked.

Formal Gardens

The formal garden of Amun-Re, Thebes (TT96), 1834, New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Formal memorial gardens like the one depicted on the walls of Nebamun were a regular feature of royal and upper-class tombs and were often constructed adjacent to temples. A model of a garden, rather than an image of one, was discovered under the floor of the tomb chapel of Meketre, chancellor to King Mentuhotpe. It depicts a garden with a pond surrounded by trees and a small house.

The formal gardens represented in tomb scenes, those known from texts, illustrations, and those found during excavations, show that they were primarily symmetrical in design and located close to private homes and tombs, palatial residences, cult centres, temples, and shrines. Typical upper-class gardens were formally arranged in the walls of their tombs because the owner of the tomb hoped to continue to enjoy his garden in the afterlife.

Of course, the fashion for gardens started at the top with the pharaohs, who often gifted them to members of the royal family or valued officials. Palace gardens were lavish with facilities for sports, leisure, music, song, and dance performances. Boats were rowed on their vast lakes, and memorial meals, wakes, banquets, and religious festivals and rituals were celebrated there. The grounds were also used to grow food, flowers, herbs, fish farming, fruit and vine cultivation, and beehives were provided to make honey.

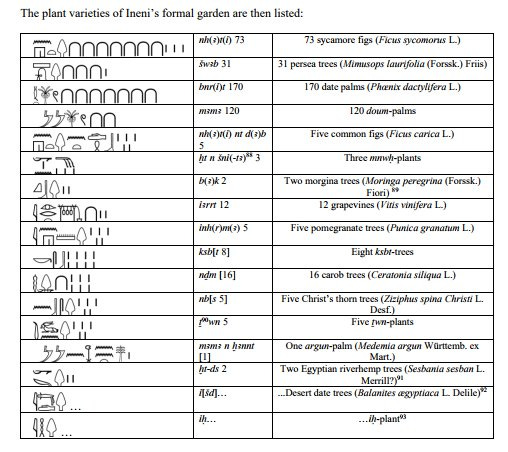

Jayme Reichart of the American University in Cairo catalogued and analysed 11 gardens constructed before the Amarna Period. An example of the number of trees of each type is listed. Each of the 42 floral and 11 animal species identified in these formal gardens had a specific symbolic meaning and a growth and development cycle, chosen so that they would be in bloom and available for harvest throughout the year. The number of plant types (42) most probably represents the idea of the land of Egypt. Forty-two is frequently associated with the concept of the whole country; for example, there are 42 Nomes, 42 Judges in the Hall of Judgement and 42 Books of Thoth.

(TT 81) (Helk, Otto, p. 891:892)

The sycamore fig, for example, was associated with the goddesses Hathor, Isis, and Nut. These goddesses were sometimes depicted as trees, standing in front of them with water vessels, or sometimes as a tree with human body parts, such as an arm or breast. The sycamore fig was the most frequently depicted life-giving tree in ancient Egypt. There are also references to twin turquoise sycamores (a metaphor for two blue columns representing the parting of the waters of Nun) in funerary contexts from which the sun god Re comes forth reborn at dawn.

Tomb image of a sycamore tree surrounding Hathor.

From the Predynastic Period onward, pomegranates formed a significant part of grave goods, but proof of their cultivation only dates to the 18th Dynasty. Images of pomegranates figured on the walls of tombs and temples and were also presented as food offerings on sacrificial altars and offering tables. The first image of a pomegranate appears in tomb TT 81 (in the Theban necropolis) in the tomb of Ineni, who worked for Amenhotep I and Thutmose I as an administrator and architect. The plan of his tomb garden included twenty different kinds of trees, including 73 sycamore trees, 170 date palms, 120 doum palms, 5 fig trees, 12 grape trees, 5 pomegranate trees, 8 ksbt trees, 16 carob trees, 5 Christ’s Thorn trees, 5, twn plants, 1 argum palm, 2 river hemp trees, and an unknown number of ished trees. From a sacred number point of view, the numbers chosen for the individual species of plants show a strong connection with 2,5 and 8 - all numbers connected with rebirth through the primordial waters of Nun. (I’ll explain more in later posts.)

Gardens were also associated with love and eroticism and were often mentioned in ancient Egyptian love poetry. Love, poems and erotic stories were frequently set in gardens, orchards, and parks where lovers met and where music, drinking, and dancing took place.

It [the sycamore tree] put a message in the hand of the young girl, The daughter of the Overseer of trees (And) made her rush to the beloved:

“Come, spend some time among the youths, The vegetation celebrates its day, A pavilion and a tent are under me, Your gardeners are joyful, They rejoice at the sight of me.

Have your servants brought in front of me, Equipped with their instruments.

One will be drunk (just) by running to me, Before having drunk.

Listen to me, Make them come carrying their equipment, So that they may bring all kinds of beer, All sorts of bread,

Numerous vegetables from yesterday and today, All fruits for enjoyment.

Come and spend a beautiful day, Morning after morning for three days, While you are seated in my shade.

Her companion is on her right, While she is making him drunk, Following what he says.

The room of beer is confused with drunkedness, She remains with her lover.

Her secret is under me, When the girl takes her stroll.

I [the sycamore tree] remain discreet, not saying what I see. I will not say a word.

(Papyrus Turin 1996, the beginning of the Twentieth Dynasty, from Deir el-Medina, Thebes).

A scene from the tomb of Ipy (at Thebes, Eighteenth Dynasty – 1,550-1,295 BC) shows a man using a shaduf to water a garden. In the image, we can see a sycamore tree, two other types of tree, papyrus flowers, and two types of water lily.