What did the Egyptians Wear and Why?

Ancient Egyptian Attitudes to the Body, Colour and the Divine

Ancient Egyptian clothing was practical and deeply symbolic, reflecting the wearer’s social class, profession, and even the religious or festive context in which it was worn. Despite the hot climate, Egyptians of all social classes dressed in ways that demonstrated their societal status and cultural values, often using linen as their primary textile. In this article, I will explore ancient Egyptians' everyday wear, coloured linens and festival attire, focusing on how different social classes expressed themselves through clothing.

Attitudes to the Body and Clothing

Attitudes towards the human body and clothing were deeply intertwined with their environment, spirituality, and social hierarchy. Clothing in Egypt was designed to suit the hot climate, with light and minimal linen garments being the norm. Men often wore simple kilts, while women donned straight, sheath dresses. Both were primarily made of linen, valued for its lightness and breathability.

However, clothing was not just functional; it also held symbolic significance. Egyptians viewed the human body as sacred and divine, emphasising maintaining purity and cleanliness, which was reflected in their clothing. Linen, made from flax, was chosen for its purity and connection to the earth, and it was also used in religious rituals and burial practices.

The way Egyptians dressed also served as a marker of social class. The elite adorned themselves with finely woven, pleated linens and elaborate jewellery, while the lower classes wore simpler garments. Adornment with jewellery was particularly significant, serving aesthetic and spiritual purposes, with certain amulets believed to protect from harm.

Everyday Wear: Practicality Meets Status

For everyday life, clothing across Egyptian society was fairly simple, designed to offer comfort in the intense heat. Linen, made from the flax plant, was the fabric of choice, as it is light and breathable and could be woven into a variety of textures and qualities, depending on the wearer’s status.

Lower Classes: Most ancient Egyptians were labourers, farmers, and artisans. These individuals wore simple, functional clothing designed to keep them cool and allow for ease of movement. Men typically wore a short linen kilt called a shandy, fastened around the waist with a belt. Women of the lower classes wore sheath dresses that extended from the chest or waist down to the ankles, often secured with straps over the shoulders. The linen used for these garments was coarse, and the clothes were unadorned due to limited access to resources for decorative elements.

Children often went without clothing until adolescence, especially in rural areas. This practice was partly due to the hot climate and the informal nature of rural life.

Middle Classes: Artisans, scribes, and merchants who occupied the middle class wore clothing similar in structure to the lower class but with more refinement. The linen used was of higher quality, sometimes bleached to achieve a pure white look—a symbol of cleanliness and, by extension, moral purity. Men of this class often wore more elaborate kilts or long tunics, while women continued to wear sheath dresses, sometimes with pleated or fringed details that indicated a higher social standing.

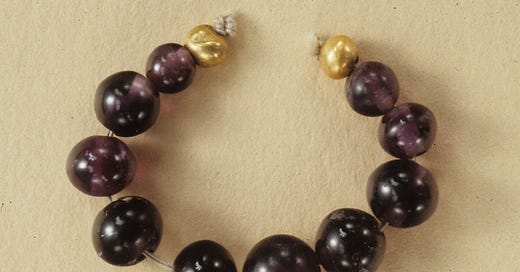

Jewellery became more common among the middle classes, often made from copper or faience (glazed ceramic beads) to show wealth and personal taste. Middle-class Egyptians could afford decorative accessories like collars, bracelets, and earrings, which helped differentiate them from the lower classes.

String of beads, Middle Kingdom, ca. 1878–1840 B.C. Met Museum

Upper Classes and Nobility: The elite members of Egyptian society, including high-ranking officials, priests, and nobles, wore clothing that reflected their wealth and status within the religious and political spheres. Men often donned long kilts or pleated robes made from fine linen, while upper-class women wore intricately pleated dresses with elaborate draping and accessories.

Upper-class clothing was often semi-transparent, showcasing the fine quality of the linen. Both men and women adorned themselves with large amounts of jewellery made from gold, precious stones, and intricately designed faience. Wigs, made from human hair or plant fibres and often perfumed with scented cones on top of the head, were a standard feature for the upper class.

In ancient Egypt, linen was the primary fabric used for clothing across all social classes, but the colour and quality of the linen varied greatly depending on status, occasion, and symbolic meaning. While undyed linen in its natural off-white or light beige colour was most common, the use of coloured linen became increasingly important for special occasions and members of the upper class and priesthood. Each colour had symbolic associations connected to religious beliefs, purity, and societal status. Let's explore the significance of various linen colours and what they represented in ancient Egypt.

1. White Linen: Purity and Divine Connection

White linen was the most common and revered colour in ancient Egypt. White symbolised purity and cleanliness and was strongly associated with divine and religious practices. For this reason, priests and priestesses almost exclusively wore white linen, particularly during temple rituals and religious festivals. Wearing clean, unblemished white linen was believed to bring the wearer closer to the gods and help maintain spiritual purity.

In Isis and Osiris, Plutarch describes the white linen worn by the priests of Isis, highlighting its symbolic significance. The priests were distinctively known for their shaved heads and white linen garments. Linen was considered a symbol of purity, as it was made from flax, a plant that grew from the earth, representing simplicity and cleanliness. The priests avoided woollen garments because wool was derived from animals, which could be associated with impurity.

The choice of linen was practical and spiritual, reflecting the Egyptian reverence for cleanliness and purity in their religious rites. This symbolism of purity extended to the priests' conduct, as they were expected to lead lives of abstinence and cleanliness in devotion to the gods.

In everyday life, upper-class Egyptians often preferred fine white linen, sometimes semi-transparent, to symbolise their moral purity and social status. Bleaching linen to achieve a whiter appearance required effort and resources, making it a luxury for the wealthy. It also indicated a commitment to hygiene, highly valued in Egyptian culture.

2. Red Linen: Vitality, Power, and the Chaotic

Red was a colour of intense, often dual, significance in ancient Egypt. On the one hand, red was associated with vitality, energy, and life force, making it a popular colour for physical strength or protection. Red linen was sometimes worn during festivals, particularly those celebrating fertility or renewal, where the colour symbolised the energy of life. Red was the colour of the sun god Re and was associated with life and protection. The red cloth was given as a daily offering to the gods in the temples.

On the other hand, red was also linked to chaos and danger. It was the colour associated with the desert, the realm of the god Set, who represented disorder and conflict. In specific ritual contexts, red linen might invoke or control chaotic forces. Because of these associations, red linen was used more sparingly and intentionally than white.

Red cloth was used for mummy wrappings in the Old Kingdom (2700-2200 BC). Analysis shows the fabric was dyed with red ochre at Khenmit and Ita at Dashur. Iron oxide was also used to dye votive animal mummy wrappings from the 3rd century BC to the 3rd century AD.

3. Blue Linen: Water, Sky, and the Divine

Blue linen, known as "IRTYW," was particularly notable for its religious significance. This blue linen fabric appeared as early as the Old Kingdom, and its use extended beyond the worldly into the spiritual realm, where it held ceremonial importance. One of its essential functions was as an offering in religious rituals.

Blue fabric was relatively rare in ancient Egypt and symbolised the life-giving forces of the sky and the Nile River. The colour blue was deeply connected to the gods, particularly those related to the heavens and water, such as the sky god Horus and the fertility god Hapi, who personified the Nile.

Wearing blue linen, particularly during festivals dedicated to these deities, was a sign of respect and devotion. It also symbolised protection, as blue was thought to ward off evil. Pharaohs and high-ranking officials sometimes wore blue to align themselves with the heavens' divine powers and display their elevated status.

Estate Figure, Middle Kingdom, ca. 1981–1975 B.C., On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 105

4. Green Linen: Fertility, Rebirth, and the Afterlife

Green was the colour of growth, fertility, and rebirth, tied to the life cycle and the agricultural abundance of the Nile’s floods. In religious contexts, green linen represented regeneration and eternal life, making it a fitting colour for rituals associated with the afterlife and Osiris, the god of the dead and rebirth.

Green linen was also symbolic of vegetation and renewal, which meant it might be worn during ceremonies connected to agriculture, harvests, and fertility. The symbolism of green linen extended into burial practices, where it was used to wrap mummies or during rituals intended to ensure the deceased’s rebirth in the afterlife.

5. Yellow and Gold Linen: The Sun and Immortality

Yellow and golden linen represented the sun, warmth, and connection to eternal life. The sun god Ra was one of the most important deities in ancient Egypt, and the colours associated with him carried deep significance. Gold, in particular, was considered the flesh of the gods, symbolising immortality and the everlasting light of the sun.

While pure gold was a material reserved for jewellery and regalia, yellow and gold-dyed linen could evoke similar associations and was worn during ceremonies dedicated to Ra or other solar deities. Wearing yellow linen signified alignment with the divine powers of the sun and the hope for eternal life, making it a popular choice for festivals celebrating the sun’s regenerative powers.

6. Black Linen: Death and the Fertile Earth

Black was associated with death, the afterlife, and the fertile soil of the Nile’s inundation. While it might seem contradictory, black symbolised the mystery of the underworld and the promise of rebirth. Black linen was rare and used in funeral rites or for special rituals related to the afterlife.

Black linen was connected to Osiris, the underworld god, as it reflected his embodied cycle of death and renewal. In some contexts, mourners or priests wore black linen during funerary practices to signal reverence for the deceased’s journey into the afterlife and hope for resurrection.

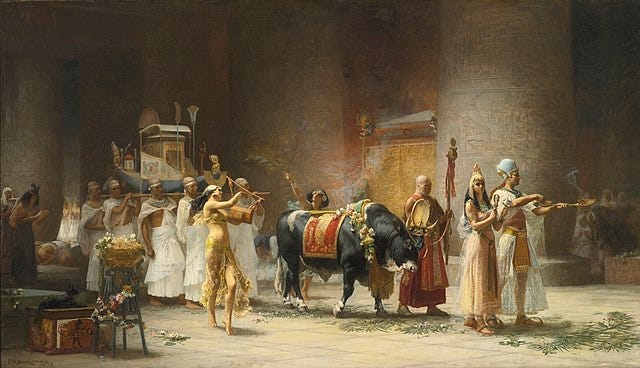

The mummification of the Apis bull, a sacred animal in ancient Egypt, followed highly ritualized procedures, mirroring the process used for humans. Although not widely documented in the results, the use of black linen in this context seems tied to symbolic and ceremonial purposes, especially in reference to the Apis bull's mummification.

The Vienna Papyrus (Papyrus Vindobonensis) is an essential source for understanding the embalming rituals. It provides a detailed account of the practices involved in the mummification of the Apis bull. This sacred document records the methods used to preserve the bull and the materials involved, including various types of linen, though specific mention of black linen remains rare in the sources currently available.

The colours of linen in ancient Egypt were much more than aesthetic choices—they were imbued with deep symbolic meanings tied to religion, the natural world, and societal values. While white linen was the standard for everyday wear, symbolising purity and divine favour, other colours like red, blue, green, yellow, and black played special roles in religious and festive contexts. Egyptians communicated their beliefs, aspirations, and social status through these colours, making clothing a key component of their identity and spirituality.

Festival and Special Occasion Attire

During festivals, religious ceremonies, and other special occasions, the clothing of all social classes became more elaborate. Egyptians believed that festivals were times to honour the gods, so they dressed in their finest attire, often incorporating unique fabrics and accessories.

Even the lower classes wear their best clothes, typically new or clean linen garments, on special occasions. Women might wear brightly coloured sashes or add decorative beadwork to their sheath dresses, while men don freshly pressed kilts. Though made from less expensive materials, Jewellery was worn more frequently during festivals.

For the elite, festivals and religious ceremonies were opportunities to display wealth and devotion. Nobles would wear their most expensive clothing, sometimes dyed with rare colours such as blue or green. Men wore pleated kilts with longer tunics, and women’s dresses became even more intricate with complex drapery, often incorporating gold threads.

During religious festivals, priests and priestesses wore special vestments that were meticulously maintained and symbolic of their sacred duties. White linen was essential in religious contexts, as it was seen as a symbol of purity. Additionally, ceremonial wigs and jewellery made from gold, silver, and precious stones adorned the upper class, making them stand out during these communal gatherings.

Clothing in ancient Egypt was a powerful marker of identity, status, and religious belief. While the lower classes wore simpler, functional clothing, the upper classes embraced elaborate garments and accessories that reflected their high status and proximity to the divine. During festivals and special occasions, clothing became even more significant, as all classes dressed to honour the gods and showcase their place in society. Whether simple or luxurious, Egyptian clothing was always imbued with meaning beyond mere functionality, making it an integral part of daily life and ceremonial events.

Fascinating deconstruction of the white-blue-red linen choices and their significance in Ancient Egypt. Thank you!