Ancient Egypt's sacred numbers remain a tantalising mystery for Egyptologists. Inscribed on grand monuments and preserved in ancient papyri, these numbers—1, 3, 7, and 12—hint at a worldview steeped in cosmology, magic, and divine order. Yet, we don't fully understand them. THIS IS BECAUSE THEY HAVE BECOME A PROFESSIONAL TABOO SUBJECT.

While Greek numbers are easy for us to comprehend because they are embedded in the Western mathematical tradition, how the Egyptians used and understood numbers remains unknown beyond what is immediately apparent. In other words, beyond simple arithmetic.

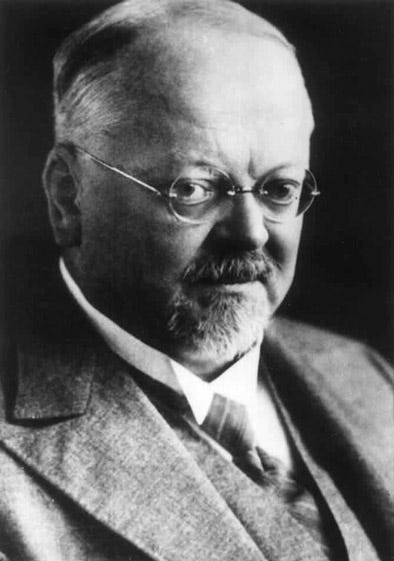

Kurt Sethe, a German Egyptologist, published one of the few works on the topic, Von Zahlen und Zahlworten bei den alten Ägyptern, in 1916.

Kurt Sethe

Sethe notes that the Egyptian number system is based on a scale of 10 that could be written in any one of three scripts – hieroglyphics being the oldest followed chronologically by hieratic and demotic. Although the most difficult to write, Hieroglyphics were used for monumental inscriptions and sacred texts from the very first dynasties to the last. Indeed, the last inscription in hieroglyphics, the Graffito of Esmet-Akhom, was written on the temple walls at Philae in 394 AD, two years after the Roman Emperor Theodosius ordered all the pagan temples of the Empire to be closed. The inscription, written in both hieroglyphs and demotic, is dated to the Birthday of Osiris, year 110 (of Diocletian), equivalent to August 24, 394.

Hieratic, a form of hieroglyphics with more rounded forms that could be written with a reed pen, emerged in the eighth century BC and was followed by demotic script, a form of more abbreviated cursive writing, which was used until the end of the Christian Era, around 750 AD.

The Number Hieroglyphics

The hieroglyphic symbols were a single line for 1, the image of a cattle hobble for 10, the image of a coil of rope for 100, the image of a lotus flower for 1,000, the image of a baboon's finger for 10,000, the image of a tadpole for 100,000, the image of the god Heh 1,000,000, and the image of a shen ring for 10,000,000.

Paid Subscribers will be able to read about the meanings of these symbols for the first time in early 2025.

The First Sacred Numbers to be Identified

While engaged in what was primarily a linguistic and philological exercise, Sethe noted that numbers, such as 1, 3, 7, and 12, also held deep religious significance beyond that of their arithmetic value. For example, he concluded one symbolised the concept of unity, seven was associated with magic, and twelve was linked to the division of time and the idea of completeness. He also connected numbers to Egyptian deities and cosmic principles, such as the number nine with the Great Ennead of Heliopolis, the gods Atum, Shu, Tefnut, Geb, Nut, Osiris, Isis, Set and Nephthys. (Horus and the sun god Re fall outside the Ennead or Nine for reasons that will be explained in future publications.) Sethe's work remains a foundational study in the field; though modern Egyptologists continue to debate and expand upon his interpretations, little progress has been made.

No Progress for a Hundred Years

The Cursed Discipline & its Taboos

The reasons for Egyptology’s lack of progress in understanding Egypt’s sacred number systems lie in the history of the 'Cursed Discipline.'1 As Juan Moreno2 pointed out in his article on the subject, Steven Spielberg's movie Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) and Anthony Minghella's The English Patient (1996) were huge successes because they tapped into the worldwide fascination with ancient Egypt, archaeology and adventure. The history and romance of Egypt's desert landscape and its vast monuments appeal like no other; consequently, mad stories abound about ancient aliens building the pyramids or the superintelligence and higher spirituality that enabled the ancient Egyptians to perform feats of mathematics and engineering so complicated today’s Egyptologists cannot understand them.

Unfortunately, Egyptology has been plagued by such stories since it began. As Erik Horung points out, after World War I, there was a surge of speculative theories about the Great Pyramids, attributing advanced scientific knowledge to the ancient Egyptians. Some claimed that the pyramids were sophisticated instruments, like stone calendars or observatories, and that the Egyptians understood concepts such as the heliocentric model of the solar system. Peter Tompkins argued that Alexander the Great deliberately destroyed Heliopolis, a centre of Egyptian science, to shift focus to Alexandria. Despite efforts to debunk these ideas, such as Ludwig Borchardt's 1922 lecture against "numerical mysticism" regarding the Great Pyramid, mystical and pseudoscientific explanations persisted.3 Notable works include Georges Barbarin's 1936 book and Adam Rutherford's Pyramidology series, which linked the Great Pyramid to Biblical revelations. Speculations continued into modern times, with figures like physicist Luis Alvarez searching for hidden chambers using cosmic rays and engineers proposing alternative uses for the pyramids, such as irrigation systems or devices for harnessing cosmic energy. These ideas contributed to an enduring fascination with the pyramids, leading to treasure hunts, theories about their supernatural construction, and claims of their mystical healing powers.

This torrent of nonsense continues today across all media.

The Desire to be Taken Seriously

Turning to the social sciences and anthropology

Whether because of the nonsense or simply a desire to be taken seriously, Egyptology decided to follow anthropology on questions of religion and what was sacred.

Anthropology, archaeology, and the social sciences, particularly those of the French philosopher and father of Sociology Emile Durkheim and the Austrian logical positivist school of thinking, have profoundly affected archaeological thinking since Borchadt’s anti-number magic declaration in 1922.

Durkheim believed religion was not so much ‘the opium of the people’ but the social glue that bound society together; he was not interested in religious belief systems per se. Working at the end of the nineteenth century, when Europe was in the throes of its industrial revolution and was experiencing mass migration into towns, Durkheim and his followers were interested to know how societies worked because they were afraid their own was about to disintegrate into chaos. As logical positivists, however, they were only interested in what could be observed, measured, tested, and proved. They saw religious language as defective, arguing that statements such as "There is a God" were empty because they could not be proved true or false.

Psychologist Sigmund Freud added to the social scientist’s distaste for the spiritual and religious when he wrote that religious belief was an illusion based on a childlike yearning for a father figure. Freud’s reasoning on the origin of religion was bizarre. In past times, he said, a father who monopolised all the women in the tribe was killed and eaten by his sons. The sons felt guilty about eating the man who had created them and started to venerate their murdered father. All this, together with taboos concerning cannibalism and incest, generated the first religion. Freud’s assessment of religion confirmed to those espousing the scientific frame of mind that its origins were primitive and base; it was a view that fitted precisely with the prevailing colonialist mindset that saw the peoples of their colonised lands as primitive and base.

The French anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss (1908-2009) has influenced Egyptologists from the former Eastern Bloc. Strauss believed our most fundamental beliefs came from our use of language. He founded what has become known as structural anthropology through a series of publications such as The Elementary Structures of Kinship (1949) and The Savage Mind (1966). In these books, he laid out the theory that the structures underlying both “civilised” and “primitive” societies are identical and that language and thinking were based on binary opposites, an idea that Egyptologists have adopted to explain many aspects of ancient Egyptian religion. The followers of Strauss claim that the ancient Egyptian religion is an attempt to reconcile oppositions such as life and death and good and evil. This Straussian logic pits agriculture and warfare against each other, with hunting as a mediator between the two because it shares the agricultural characteristics of obtaining food with the physical violence of warfare. Its application to the ancient Egyptian religion has reduced it to a mechanical battle between competing opposites that must be reconciled by moderating influences to achieve the harmonious state of ma’at.

This human-centred, mechanical approach to religion continued in anthropology well into the late twentieth century when academics such as Bronislaw Malinowski and Clifford Geertz were crucial influencers. Malinowski argued that the primary function of religion was to help individuals and society deal with the emotional stresses that accompany life’s crises, such as birth, puberty, marriage, and death. Its role was to smooth the raw edges of human existence, operating as a sort of emotional tranquilliser, according to Malinowski. Geertz said religion was a culture of symbols that evoked feelings and beliefs that may or may not be true.

At the end of the last century, the social-scientific theories of religion were joined by theories inspired by the natural sciences, particularly evolutionary biology and cognitive psychology. In Religion Is Not About God, a book that hit the shelves in 2006, anthropologist Loyal Rue proposed that at the heart of almost all religions and cultures is a story – a myth. According to Rue, this is because we humans are emotional, narrative beings. To Rue, religion’s function is the achievement of personal wholeness and social coherence. In other words, religion has become a ‘New Age’ and is about self-actualisation, but to maintain its social science connection, it is still coupled with old-fashioned social functionalism. The mythic narratives, says Rue and their attendant practices, help to shape personal emotions and motivations in a way that allows them to overrule the innate intuitive morality of their biological heritage in favour of culturally defined values. So, religion’s function is to override our baser animal instincts.4

Thus, research into anything related to sacred numbers in ancient Egypt has become a no-go area for anyone intent on a career in Egyptology.

Histories of Egyptology, Interdisciplinary Measures, Edited By William Carruthers, Routledge, 2014.

https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780203754139-5/cursed-discipline-juan-carlos-moreno-garc%C3%ADa

Horung, E. The Secret Lore of Egypt, Its Impact on the West, Cornell University Press, 2001.

Rue, L. Religion is Not about God: How Spiritual Traditions Nurture our Biological Nature and What to Expect When They Fail, Rutgers University Press; First Paperback edition (24 July 2006).

Wonderful Julia~ thank you so much for this history lesson on why much of the sacred of the Ancients in Egypt remains undisclosed. I'm a little familiar with some of the authors as I took Anthro as a minor, and Sociology was a mandatory semester, as an undergrad. May your ka live~~~