October Newsletter

News, Updates, Symbol Poll, Book Review

News From Egypt

A Journey Through Time! The New Grand Egyptian Museum begins its trial run in the main galleries.

In October, visitors will have the opportunity to explore 12 meticulously curated exhibition halls of the main galleries, showcasing the evolution of Egyptian civilisation from prehistoric times to the Roman era. The museum is open daily from 8:30 a.m. to 6 p.m., with ticket sales closing at 4 p.m. Ticket prices vary based on category, with admission starting at EGP 200 for Egyptians, EGP 1,200 for Arabs or other nationalities, and EGP 600 for expatriates. Discounts are available for children, students, and seniors.

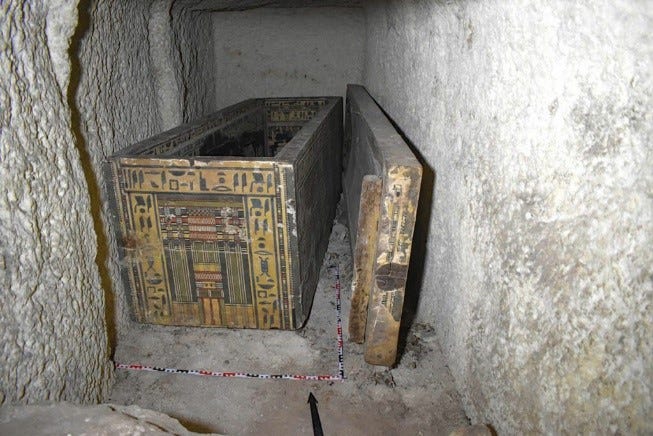

Discovery of the tomb of Edi, daughter of Jifai-Hapi, governor of Assuit during the reign of Senwosret I

This month, Ahram Online reported that a tomb dated to the 12th Dynasty was discovered on the west bank of the Nile River in Upper Egypt's Western Assiut Mountain by a team of researchers from Sohag University and Berlin University. The tomb belonged to Edi, the daughter of Jifai-Hapi, the governor of Assuit during the reign of Senwosret I (1961 to 1917 B.C.) The researchers discovered Edi's tomb while excavating her father's tomb. "Preliminary studies suggest that Edi died before reaching the age of 40 and suffered from a congenital foot defect," said Mohamed Ismail of the Supreme Council of Antiquities. The fact that she was in her late thirties and buried with her father suggests Edi never married or had children of her own. Perhaps Edi's foot defect was an obstacle to her finding a husband. To add to her misfortune, Edi's tomb was looted in antiquity. Her remains were damaged, and her canopic jars smashed. She was buried in two wooden coffins, one inside the other. Both were painted with texts describing the journey to the afterlife.

Figure 1 Edi's Coffin

Newly Discovered Nile Carvings Link Amenhotep III, Thutmose IV, and More to Aswan's Ancient Quarries"

Recently discovered carvings in the Nile near Aswan highlight the reigns of notable Egyptian rulers, including Amenhotep III, Thutmose IV, Psamtik II, and Apries. Amenhotep III, one of Egypt's most powerful rulers, oversaw a prosperous era and monumental architecture, including his mortuary temple. His son, Thutmose IV, is famous for restoring the Great Sphinx. Psamtik II, a later pharaoh, led military campaigns into Nubia. Meanwhile, Apries faced internal strife, eventually being overthrown.

The images include pictures of Amenhotep III (reigned ca. 1390–1352 B.C.), Thutmose IV (reigned ca. 1400–1390 B.C.), Psamtik II (reigned ca. 595–589 B.C.), and Apries (reigned ca. 589–570 B.C.).

The Aswan quarries were crucial for Egypt, providing granite for temples, obelisks, and monuments, connecting the region to Egypt's architectural grandeur. The newly discovered carvings confirm the importance of this quarry site, which was once a bustling centre of royal projects. Archaeologists are recording these rock carvings using the latest digital technology and ensuring their physical preservation.

Figure 3. Inscriptions at Aswan, Photo: Archaeology News, 2024.

Ancient Military Barracks and Artifacts Uncovered at New Kingdom Fort in Egypt's Delta

A recent discovery at Tell Al-Abqain, the remains of an ancient city just south of Alexandria in Egypt's Western Delta, in what was once the Third Nome of Lower Egypt, has revealed the remains of a New Kingdom-era Fort. Constructed from mudbrick, it includes military barracks and storage rooms. The excavation team, led by Dr. Ahmed Said El-Kharadly, has uncovered a range of ancient weapons, army provisions, and the personal items of the men and women who lived and worked there, offering a unique glimpse into the lives of ancient soldiers stationed at this strategic military outpost. Artefacts like a bronze sword bearing Pharaoh Ramses II's name, ivory kohl applicators for decorating and protecting the eyes against the fierce desert sun, and magical amulets were found. One of the most intriguing finds was a cow burial, perhaps a dedicated offering to the goddess Hathor, the patron of the Nome.

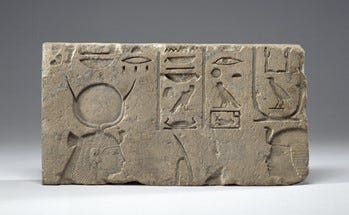

Figure 4: Walters Museum Relief

The image below shows a rare relief found at the capital of the third Nome. It shows King Necho II facing the cow-goddess Hathor, who wears a vulture headdress topped by a sun-disk and cow horns. The inscription above the goddess may once have read, "I grant you every country in submission." Dated to circa 600 BC (Late Period) the relief can be seen at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore.

These discoveries highlight the fort's role in defending Egypt from invasions from the Libyans and the mysterious Sea Peoples, who invaded Egypt and were defeated in the decisive Battle of Perire around 1208 BC.

In the late 13th century B.C. Libya faced famine. To save his hungry people, their chief, Meryey, formed an alliance with the mysterious 'Sea People', ruthless marauding mercenaries who were the surge of the civilised world. He also gathered an invasion force of thousands of men with their families and possessions and set out to invade Egypt.

At first, the Libyans advanced strategically, securing key locations like oases and splitting into columns to disrupt Egyptian defences. Their alliance with the Sea Peoples, hired possibly through Libya's control of trade, added significant strength to their endeavour. However, when they reached the western Nile Delta, they clashed with Pharaoh Merneptah's forces at Perire in 1208 BC. After a fierce battle, Merneptah's archers and chariots overwhelmed the coalition, killing thousands. Meryey's invasion was halted, and what remained of his forces limped back to Lybia.

Despite this decisive Egyptian victory, Libya remained a persistent threat. The sword found at the excavation bearing the name of Ramses II, also known as "The Great", stands testament to the Egyptian's complex relationship with the Libyans. Ramses II and his father, Seti I, campaigned against the Libyans and the Hittites. Whether the golden sword was Ramses II's will no doubt be a matter of academic debate for years to come, as there aren't any detailed accounts of his direct involvement there. Ramses II did, however, build fortresses along the western edge of the Delta and the Mediterranean littoral to monitor Egypt's western marches. These fortresses served both military and economic purposes.

Figure 5. Excavations at Tel Al-Aquid, Courtesy of the Ministry of Antiquities, Egypt.

October Diary: A Month of Sacred Numbers and Unpredictable Weather

As October draws to a close, I've been reflecting on how this month has flown by, packed with research, writing, and the inevitable juggle of life. My ongoing project on ancient Egyptian sacred numbers has taken much of my focus, and I'm thrilled to say that the book is shaping up nicely. This is the very one that I'll be serialising on Substack in the New Year, so watch this space! The deeper I delve into the significance of numbers in ancient Egyptian culture, the more I uncover their profound influence on religion, architecture, and daily life.

This month, I've also had the pleasure of sharing four new Substack articles: Did the Ancient Egyptians Have a Religion?, What Did the Ancient Egyptians Wear?, Beer Dreams and Divine Visions, and Tomb Robbery. Writing these pieces has been a joy, and I'm incredibly grateful to all of you who have read, engaged, and subscribed. Subscriptions have doubled over the last month, which is terrific, and I want to personally thank those of you who have taken the plunge and joined the community. It means the world to me!

If you're enjoying the content, I'd be so grateful if you could "restack" any posts you've liked and share them with others who might find ancient Egypt as fascinating as we do. And, of course, I always welcome feedback—what are you curious to know more about when it comes to Egypt's rich history and culture? Drop me a message; I'd love to hear your thoughts.

Next month, I'm excited to start working on my podcast and adding more to my YouTube channel, so there's plenty more to come.

On a personal note, the weather in the U.K. has been relentlessly wet and cold—hardly ideal for a sun lover like myself. With the added responsibility of caring for three elderly parents, it's been a challenging time, and I haven't been teaching as much. But even amid the unpredictability of life, there's always room for some ancient Egyptian wisdom to shine through.

Thank you all again for your support, and here's to more discoveries ahead!

Warmly, Julia

Subscriber Poll

Book Review

Empress of the Nile: The Daredevil Archaeologist Who Saved Egypt's Ancient Temples from Destruction

Lynne Olson: Random House, February 28, 2023

This is a remarkable chronicle about the fearless French archaeologist who spearheaded the international mission to save ancient Egyptian temples from the rising waters of the Aswan High Dam.

Written by the acclaimed author of Madame Fourcade's Secret War, this gripping account highlights a groundbreaking moment in archaeology and heritage preservation and would make an ideal Christmas present for someone who loves everything about ancient Egypt.

Hailed as a real-life counterpart to Hollywood adventurers, Christiane Desroches-Noblecourt's courage and determination have been compared to legendary figures like Indiana Jones. Her story, however, is not fiction. In the 1960s, as global attention zeroed in on a race to rescue ancient monuments from submersion, Desroches-Noblecourt played a pivotal, yet often overlooked, role. Without her bold leadership, structures such as the Temple of Dendur—now showcased in the Metropolitan Museum of Art—would be lost beneath a massive reservoir.

The campaign was a monumental challenge, involving the painstaking dismantling and relocation of fragile sandstone temples to higher ground. Desroches-Noblecourt, known for her fierce independence and resolve, was no stranger to taking on powerful figures. A veteran of the French Resistance during World War II, she had survived Nazi imprisonment and later stood her ground against influential postwar leaders, including Egypt's President Abdel Nasser and France's President Charles de Gaulle.

Unexpected support came from Jacqueline Kennedy, who convinced President Kennedy to back the project financially. In an era when Western powers had long been criticised for exploiting Egypt's treasures, Desroches-Noblecourt's efforts helped preserve a priceless cultural legacy for future generations.

Reviews

"Olson relates in this fast-paced, highly entertaining book. The highlight of Olson's book is her thrilling account of the rescue of the giant statues of Rameses II and the Abu Simbel temples from inundation by the Aswan High Dam."--The New York Times Book Review (Editors' Choice)

"Olson, whose many previous books spotlight unsung heroes and heroines of that war, is here at her best . . . Empress of the Nile tells her story well, embedding it in the history of modern Egyptian archaeology. Empress of the Nile is a welcome and needed work of both rescue and reclamation."--The Washington Post