The all god, the flamingo and the egg

What's the connection and why are they important to our understanding of Ancient Egypt?

The All-God, the Flamingo, and the Egg: What They Tell Us About Ancient Egypt

In the beginning, there was the flamingo, or was it the egg? This age-old paradox has fascinated philosophers, scientists, and religious thinkers for centuries. At its heart, this question explores the nature of causality, origin, and the cyclicality of life, asking whether the first chicken emerged to lay the egg or if the egg existed first to hatch the chicken. This riddle delves into concepts of infinite regress—an endless chain of events without an identifiable beginning—making it a powerful metaphor for deeper philosophical inquiries into the origins of existence and the natural order.

The modern scientific perspective, informed by evolutionary biology, proposes that the egg likely came first. According to evolutionary theory, a bird species similar to a chicken would have laid an egg with genetic mutations that led to the first actual chicken. This answer, however, doesn’t diminish the philosophical or symbolic weight of the question. It continues to be a powerful illustration of humanity's pursuit of understanding causality, the origins of life, and the mysteries underlying existence itself.

Religiously, interpretations of the question often reflect creationist beliefs. In many Abrahamic traditions, for instance, the concept of a divine Creator who sets all processes into motion can lead believers to argue that the chicken (as part of God’s creation) must have come first. Within Christian theology, the Genesis narrative suggests that animals were created in their mature forms, which can be interpreted as a theological basis for the chicken preceding the egg. This perspective aligns with views of divine causality, where creation starts with a purposeful design rather than a natural progression.

Eastern religions and philosophies like Hinduism and Buddhism offer alternative insights. Hinduism’s cyclical view of time suggests that life and creation are endless cycles without absolute beginnings or endings, making the chicken-and-egg question less about a linear sequence and more about the perpetual dance of creation and rebirth. Similarly, in Buddhism, the question can be seen as a kōan—a paradoxical or unanswerable question meant to encourage meditative insight and transcend ordinary logic, pointing to the mystery of dependent origination or the interconnectedness of all things.

But if we go back to figures like Aristotle, who approached this question from a biological and metaphysical perspective, I think we can begin to understand how the ancients approached it. Aristotle concluded that neither the chicken nor the egg could truly come first; instead, he posited they have always coexisted as part of an eternal cycle. This aligns with his broader belief in a universe with no beginning or end, an idea that resonates with some philosophical traditions about existence being inherently cyclical. Indeed, we can see the essence of this cyclical approach to life, death and rebirth as early as the Pre-dynastic Period. The trouble is Egyptologists have misread the signs.

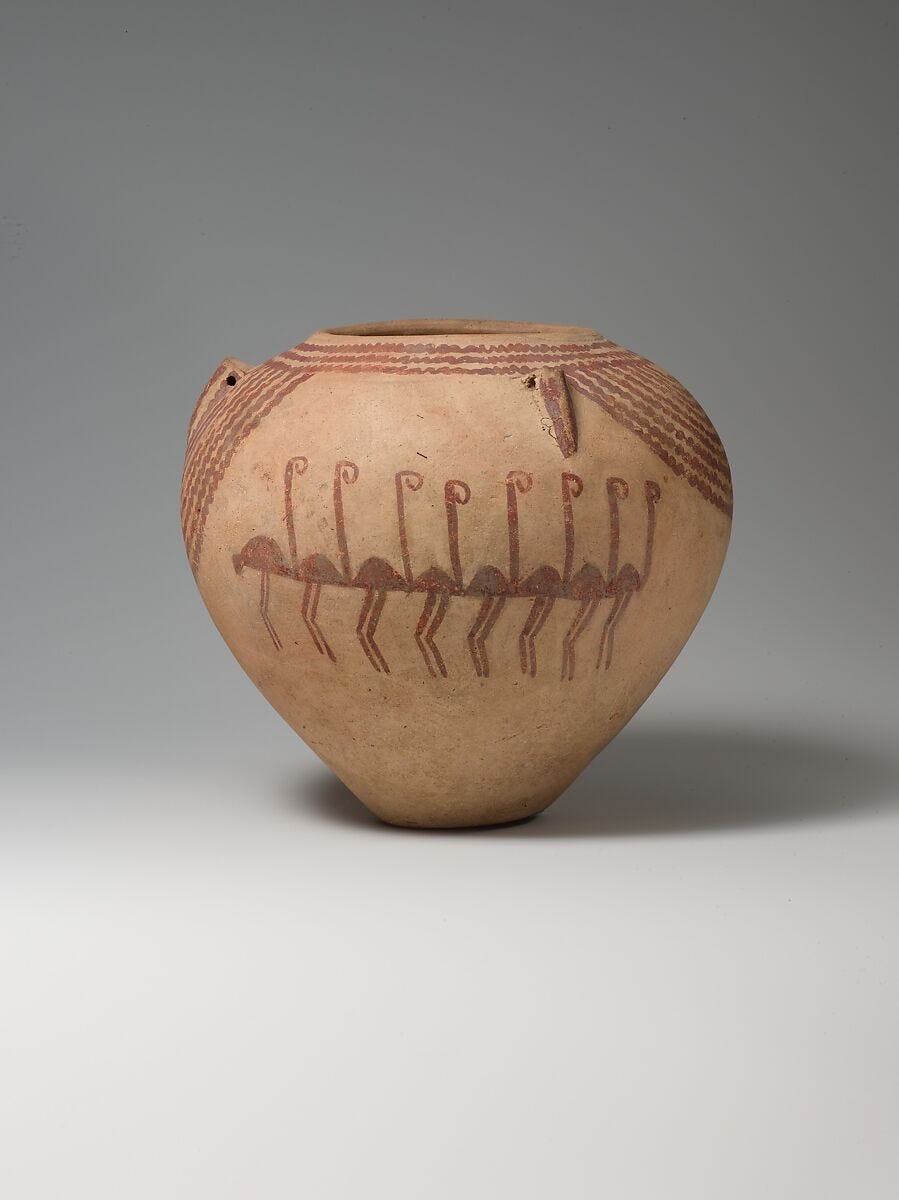

Decorated ware jar depicting rows of flamingos, Predynastic, Naqada II, ca. 3650–3300 B.C. On view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 101

In 2011, leading French Egyptologist Beatrix Midant-Reynes wrote an article entitled "Domesticates and Wild Game in the Egyptian Western Desert at the End of the 5th Millennium BC." People and Animals in Prehistory. In the article, she and other leaders in the field explored the interaction of symbolic elements, such as flamingoes on predynastic pottery with animal motifs, positing that these images reflected a connection with natural elements and rituals relating to fertility, hunting, and social hierarchy. Maidant-Reynes calls all of the animals on the pots riverine, which is associated with the freshwater of the Nile.1 2In doing this, these eminent academics follow the strictly materialist and functionalist approach to religion that now dominates academia. However, I believe they are wrong, especially regarding flamingoes.

The red-pink flamingoes we love to see when we visit the zoo do not live in freshwater in the wild. Wild flamingoes live on shallow salt and soda lakes, estuaries, and mangrove swamps, environments rich in algae, crustaceans, and diatoms that give flamingos their characteristic pink colour. In Egypt, they lived on its natron lakes, particularly those in the Wadi El-Natrun region, west of the Nile Delta and around Hermopolis Magna in the Nome, whose patron was Thoth, the moon god.

Natron is a naturally occurring mixture of sodium carbonate, bicarbonate, and small amounts of sodium chloride and sulfate. The ancient Egyptians harvested it for mummification and the ritual cleansing of their holy places, which were essential to their funerary customs.

Although flamingos can breed year-round, they often coordinate breeding seasons when conditions are optimal. Monogamous by nature, flamingo pairs engage in elaborate courtship displays, including synchronised dancing and head-flagging rituals. The dance begins with sometimes thousands of birds head-flagging in a coordinated, rhythmic motion. This is followed by "wing salutes," where the birds spread their wings wide to reveal their vibrant pink and black feathers, often lifting one wing higher in an arching display while turning slightly sideways.

Another notable move in the dance is the "twist-preen," where flamingos twist their heads back to touch their tails with their beaks, simulating grooming but in a ritualised, slow-motion way to draw attention. As the dance progresses, the group begins "marching" or walking together in unison, lifting their legs high with each step, creating a rhythmic, almost ceremonial progression. And so, order emerges from the swirling chaos as the mass of birds moves in lockstep around the ‘lake of flames’.

The Flamingo Mating Dance: All rights & credits BBC.

Flamingo means ‘flame’, and the lake of fire or the lake of flame becomes a highly significant part of the journey to the afterlife in later funerary texts. The "Lake of Fire" or "Lake of Flames" was a place of purification and transformation in the Egyptian afterlife, where the deceased souls cleansed their bodies of sin before reaching a higher spiritual plane. It symbolises both destruction and renewal, reflecting the dual nature of fire in Egyptian cosmology.3 In various texts, W. Van den Dungen interprets the Lake of Flames as an aspect of the sun god Re's daily path. Here, the lake is a source of rejuvenation, where Re submerges at night, only to rise renewed at dawn. Van den Dungen emphasises its role in eternal cycles, connecting human souls to cosmic rebirth patterns.4 And so, it is with the flamingoes on the Pre-Dynastic ‘D’Ware pots, which were made for funerals and deposited with the dead.

“Like men, the gods die, but they are not dead. Their existence–and all existence–is not an unchanging endlessness, but rather constant renewal. From an early period the “dead” are only the damned, that is, those who are condemned in the judgment after death, or hostile powers; to be dead is not the same as not to exist. Siegfried Morenz emphasized that “for the Egyptians constant regeneration was part of duration.” The blessed dead and the gods are rejuvenated in death and regenerate themselves at the wellsprings of their existence.”5

However, there is another connection with the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth, which is connected with the flamingo. Once paired, both male and female contribute to building a unique nest—a mound made of mud, approximately 12 inches high. The female lays one large, chalky-white egg on the mound that the pair incubates for 27–31 days (about one synodic moon cycle).

The chick emerges with soft, grey, fluffy plumage that will gradually turn pink-red and black over the next 2-3 years. Unlike many bird species, flamingo parents produce a specialised "crop milk," a nutrient-rich fluid secreted from glands lining their digestive tracts, which is bright blood red. They give so much food to their offspring that their pink-red colouring, associated with the sun in the eyes of the ancient Egyptians, sometimes dulls or disappears, reverting the bird’s plumage to black or white, the colours of its birth and associated with the moon the celestial body that dies and rises again every 29.25 days. And so the adult birds look like they are sacrificing their blood to give life to their child. This was an idea later picked up by Christian thinkers, but the bird they chose, the pelican, is a symbol which became a symbol of Christ's sacrifice for humanity because of a legend that says the pelican would pierce its breast with its beak and feed its young its blood.

So, here we see the connection between the flamingo and the cyclical waxing and waning of the moon and the symbolism of life, death and resurrection. The great cosmic egg appears on a mound from the primordial waters in the creation myths of Thebes and Memphis. It symbolised the totality of the cosmos and all life. The Ogdoad of Hermopolis carried this sacred egg to Thebes (modern-day Luxor/Karnak), where it was placed in the temple, signifying the birth of the sun god, Re (or Amun-Re in later traditions). This act marked the transition from chaos to order, with the god Re emerging as the life-giving sun, illuminating the world and initiating the cycles of day, night, and creation.

In the Heliopolitan creation myth, the world appeared when Atum stood on the mound at the beginning of time and created everything that would ever exist with the liquids of his body by masturbation, sneezing or spitting. The Benben stone, named after the mound, was sacred to the temple of Re at Heliopolis (Egyptian: Annu or Iunu). It was the location on which the first rays of the sun fell at the beginning of time and at the start of every day. It is thought to have been the prototype for later obelisks, and the capstones of the great pyramids were based on its design.

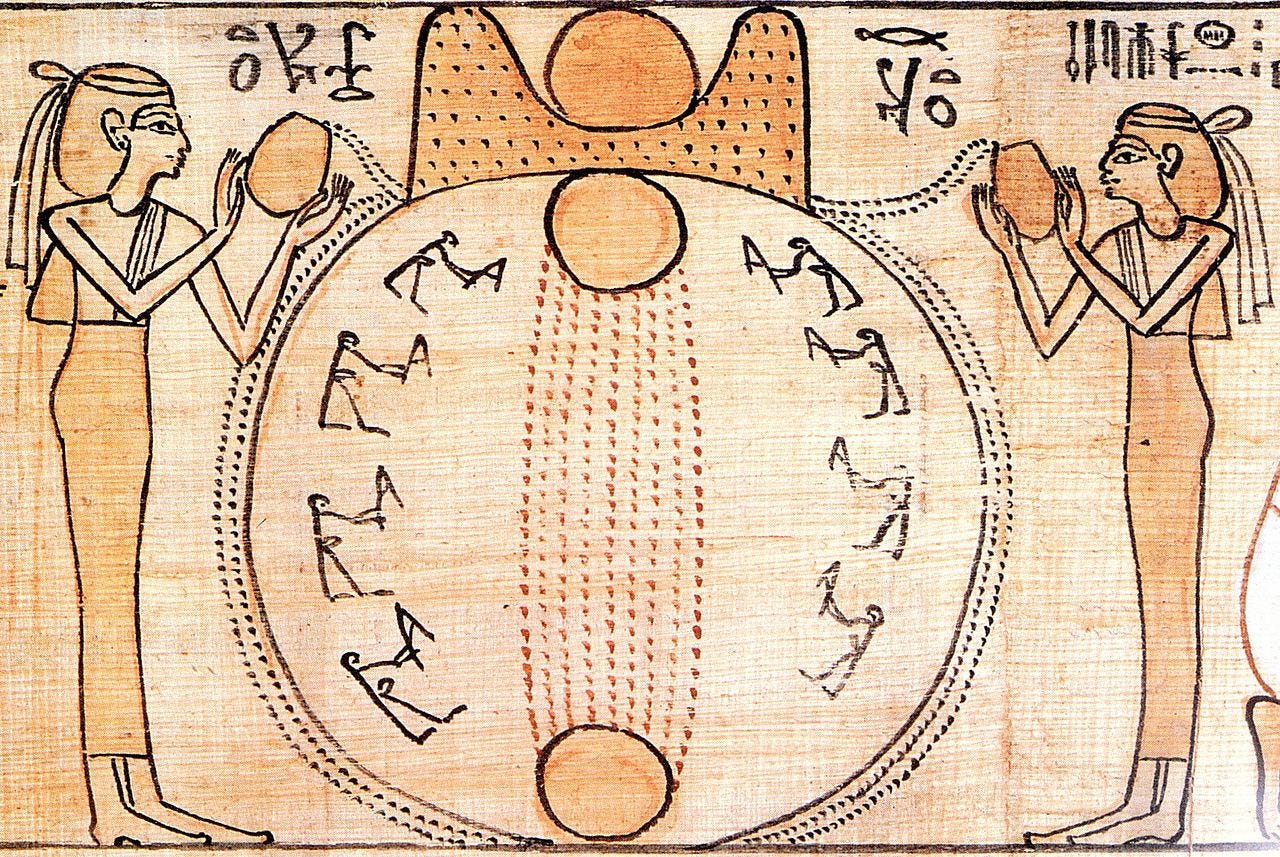

The illustration above shows the sun rising from the mound of creation at the beginning of time. The central circle represents the mound, and the three orange circles represent the sun in different stages of its rising. At the top is the "horizon" hieroglyph, with the sun appearing atop it. At either side are the goddesses of the north and south, pouring out the waters surrounding the mound. The eight stick figures are the gods of the Ogdoad, hoeing the soil.6

In both cases, the one egg of the Flamingo or Ibis and the one god Atum represent the totality of the cosmos- all that will ever be. Thus, from the one, the many will flow by a process of infinite division. “In the New Kingdom, “the one, who made himself into millions” is a common epithet of the creator (Atum) which renders this characteristic explicit. “Millions”–enormous and unfathomable but not infinite multiplicity–are the reality of the world of creation, of all that exists.”7

So, what’s this all got to do with counting? Well, it is about cultural beliefs about the origin of numbers and how numbers are made. To the ancient Egyptians, numbers were made by dividing one into many; everything that existed was thought to be a fraction of totality, whereas, in ancient Greece, numbers were made by adding one to create an infinite linear progression. The Greeks and many Western philosophers would come to wrestle with the concept of the one and the many for centuries, but it was no problem for the ancient Egyptians because, for them, the ideas of infinity and totality were entirely separate. Infinity consisted of the formless, lifeless, dark and silent waters of the Nun, which was full of potential, whereas totality was the concrete cosmos where potential was realised and filled with life and light. The egg symbolises the one or totality from which all life emerges at the beginning of time.

Furthermore, the flamingo’s vibrant dance, fiery habitat, and nurturing sacrifice encapsulated the Egyptian view of life as an eternal cycle. From the cosmic egg to the "lake of fire," the flamingo stood as a living metaphor for renewal, transformation, and the mysteries of existence—proof that even the most humble creatures could carry the weight of the divine.

So next time you see a flamingo, think not just of its beauty but of the profound truths it symbolized to the people of Ancient Egypt: that from chaos comes order, from one comes many, and that life, like the flamingo’s dance, is an endless, sacred rhythm.

Midant-Reynes, B. (2000). "The Naqada Period (c. 4000–3200 BC)" in The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt (I. Shaw, Ed.). Oxford University Press.

Midant-Reynes, B., & Buchez, N. (2007). "Decorated Ware and Predynastic Symbols in Ancient Egypt." In this study, the authors analyze the decorative elements on pottery from Egypt's Naqada period, discussing their symbolic meanings associated with rituals, status, and social differentiation in early Egyptian society.

ES Abass (2009) - The Lake of Knives and the Lake of Fire: Studies in the Topography of Passage in Ancient Egyptian Religious Literature.

W. Van den Dungen (2016) - Ancient Egyptian Readings.

E. Hornung, Conceptions of God in Ancient Egypt: The One and the Many, Trans Baines. J, Cornell University Press, p. 160, 1996.

Ancient Egypt, edited by David P. Silverman, p. 121; photograph from the Book of the Dead of Khensumose

Ibid (5), p. 170.

Love this. Though an ordinated christian Padre, I have studied Kemetic religion and am part of a kemetic society, not as priest but as a society member.