The Magic and Mystery of Life

In ancient Egypt, magic, or heka, was not an obscure or deviant practice but a fundamental force that permeated all aspects of life.

Have you ever wondered if hidden forces shape our lives, pull on our emotions, or influence our physical health? It’s an age-old question: Are there cosmic energies that influence us, unseen but deeply woven into the fabric of our world? Cultures worldwide have long believed in these invisible forces. People have sought to harness them, offering gifts, prayers, or even conducting elaborate rituals to gain favour or to shield themselves from potential harm.

The ancient Egyptians took this idea to another level, believing in heka—a cosmic power that touched everything, from the creation of the universe to the most mundane daily events. To them, heka wasn’t some mystical outsider force; it was as real as the Nile and as essential as the sun’s rise. Ancient Egyptians couldn’t imagine life without heka; theirs was not a world of cold, rational materialism or one of fearful submission to unseen gods. Their gods, after all, were trusted cosmic partners, sharing their goals of maintaining order, warding off chaos, and supporting prosperity. Heka was the bridge connecting the people and their gods, enabling Egyptians to tap into this powerful energy to ensure a good harvest, a peaceful family, or even a safe journey into the afterlife.

Magic wasn’t separated into "black" or "white" in Egypt; rather, heka was woven into the fabric of life. Only after contact with other cultures did Egyptians start to think in terms of deviant or forbidden magic. For Egyptians, the word “sorcerer” or “magician” didn’t carry the negative weight it often does today. Those skilled in heka were healers, guardians, and advisors. They worked alongside priests, kings, and even the people themselves, drawing on heka to protect, guide, and connect.

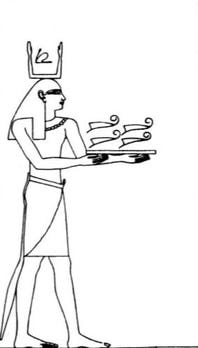

At the heart of Egyptian symbols of heka were powerful images, each with its distinct purpose. The Was sceptre symbolised dominion and was held by gods and pharaohs alike to show order and control. The ankh, a familiar symbol even today, represents life itself, often seen in art as a divine gift from gods to humans. The Djed pillar, a symbol of Osiris, god of resurrection, symbolised strength and continuity. Then there was the sa amulet, worn as a protective charm in life and death, guarding the wearer from harm in both realms. These symbols didn’t just decorate temples and tombs—they were seen as active, tangible conduits of heka, and they allowed Egyptians to channel this cosmic force into every corner of life.

Priests engaged heka through ritual and incantation, invoking the power of the gods through songs, sacred objects, and symbols. Rituals could include precise recitations from holy texts aimed at aligning the earthly with the divine. In temples, elaborate ceremonies invited gods to embody statues or objects, turning these into vessels of heka to aid in healing, protection, or guidance. Protective wands, often carved from hippo tusks or ivory, bore figures like lions and serpents to ward off evil, especially for mothers and children. Purification rituals used water from consecrated vessels, bridging people to the divine through ritual cleansing.

A 12th Dynasty wand amulet is at the Cairo Museum.

Egyptian medicine was intertwined with heka as well. Physicians—often priests—combined medicine with incantations, enhancing the healing power of their treatments. In funerary rites, heka played a critical role in ensuring a smooth transition to the afterlife, empowering the deceased with spells and amulets to protect and guide their ka, or spirit, in the next world. In every realm, from medicine to cosmic balance, heka was carefully cultivated and managed, a life force sustaining the world and bridging it to the divine.

The hieroglyph for heka includes the symbol ka (kꜣ), two and raised to the sky, representing the “vital essence” of all beings. It tells us that heka energised the ka, allowing transformation, growth, and even entry into the afterlife.

Heka’s symbolism of entwined snakes is an image of power and protection that echoes across cultures. The snake was revered as a protector due to its ability to shed its skin, symbolising rebirth, healing, and immortality. This regenerative quality gave it a mystical association with eternal life and vitality, making it a natural symbol of health and protection. Under the Ptolemys, the image of the two snakes was transferred to Hermes' caduceus and later became the modern symbol for medicine. This is a testament to Egypt’s far-reaching cultural influence.

More than a mystical practice or cosmic mystery, the belief in and practice of magic, or heka, was an integral and systematic part of Egyptian life. Managed by educated priests who served as custodians of cosmic order, heka was part of this world and the next. It was life's supernatural motivating and binding force, connecting the seen and unseen.

Bibliography:

An intriguing read Julia. I have sourced Andres text, I'm interested in learning more about the sa amulets; they sound personalised.

I couldn't find Olga's publication, but am familiar with some of her background and writings via the HarvardX course of her husband Nagy (and team)