WORDS AND NUMBERS - THE SACRED AND THE PROFANE:

How did the ancient Egyptians really think?

Have you ever wondered how the ancient Egyptians viewed the world around them?

The ancient world is a complex puzzle with many missing pieces, and how we approach solving it can be just as puzzling.

Scholars often dictate the rules, but sometimes, these rules overshadow the very mysteries we seek to uncover.

So, how should we explore what the ancient Egyptians really thought?

Understanding Ourselves to Understand the Past

It's a fact that most scholars suffer from the 'curse of knowledge' (or the effect of knowing). The more success a scholar has had in applying their knowledge, the harder it is for them to imagine alternatives, and this has been the case with many Egyptologists, many of whom have failed to challenge their long-held assumptions about the past. This lack of introspection has resulted in a history of intellectual prejudice and a narrow focus that has distorted our understanding of the fantastic world of ancient Egypt.

The Complex Web of Culture

Understanding the ancient world begins with understanding its various cultures and their unique blend of social structures, technological innovations, and belief systems of a people at a given time and place.

Culture runs deep; it's more than just identity. Identity is about questions like "Where do I belong?" and is based on shared images, stereotypes, and emotions.

Cultural identity, on the other hand, is shaped by shared experiences. It accommodates personal differences. Culture transcends race, ethnicity, and national identity.

Sacred vs. Profane: The Traditional Divide

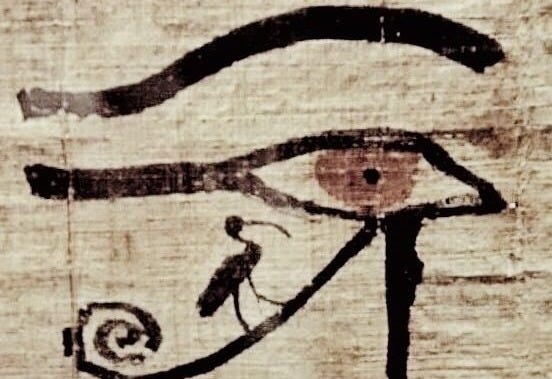

Traditionally, Egyptologists have analysed ancient Egyptian culture by dividing it into two categories: the sacred and the profane. The sacred involves elements linked to the divine, eternal, and transcendent—gods, temples, rituals, and objects like the pharaoh's regalia, believed to embody divine power. For instance, the Temple of Karnak was sacred because it was thought to be the dwelling place of gods, where priests performed rituals to maintain maat, the cosmic order.

In contrast, the profane encompasses the ordinary, everyday life aspects lacking divine significance. Today, Egyptology primarily focuses on the profane materiality of ordinary life and its ontological experiences. This approach examines daily objects, spaces, and practices to understand how they shaped and reflected the lived experiences of Nile Valley inhabitants.

The Intertwining of Sacred and Profane

However, ancient Egypt often blurred the line between sacred and profane. For example, while the Nile River was crucial for daily life and agriculture, it also had sacred connotations associated with gods like Hapi, Osiris, Sobek, and Khnum. This intertwining is also evident in burial practices, where tombs were designed as eternal homes for the dead and decorated with sacred texts like the Book of the Dead.

Words vs. Numbers: A Sacred Dichotomy?

There has been much confusion about and a general lack of interest in the sacred today, but that wasn't always the case. Egyptologists like Paul Clergg and Corinna Rossi 1 have explored the symbolic power of words, particularly in religious texts and rituals. Words, they conclude, were believed to hold magical power, invoking gods or altering reality when spoken or inscribed. Rossi emphasises the meticulous care given to hieroglyphic inscriptions, which she thinks the Egyptians regarded as sacred expressions of divine truth, contrasting with the utilitarian nature of numbers. Annette Imhausen's work on ancient Egyptian mathematics supports this view, highlighting how numbers were primarily seen as practical tools for administration and architecture, lacking the divine or mystical connotations that words carried.

Barry Kemp2 further explores how the Egyptians viewed words as living entities essential to maintaining maat (cosmic order), while numbers served more functional purposes in commerce and engineering. Kemp's analysis shows that the sacredness attributed to words underscores their importance in religious and cultural contexts, whereas numbers were relegated to the realm of the profane, used in everyday transactions and record-keeping.

The Shift in Perspective

Over the last century, Egyptologists have increasingly focused on progress and science, viewing religion as purely a social phenomenon and relegating numbers to the domain of the profane. The last Egyptologist to take ancient Egyptian numbers seriously was Kurt Sethe (1869-1934), whose work remains the go-to reference for sacred numbers in Egyptology.

In my next article, I will explain why Egyptologists have a problem with sacred numbers.

Stay Updated

To follow the latest research on sacred numbers—what they are, what they mean, and how they transform our understanding of ancient Egyptian culture—subscribe to this site.

________________________________________

Corinna Rossi: Rossi’s work in "Architecture and Mathematics in Ancient Egypt" explores how mathematical principles were applied practically in construction and administration, in contrast to the sacredness associated with written words.

Barry Kemp: Kemp's "Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization" provides insight into the importance of language and the written word in maintaining cosmic order, compared to the practical use of numbers.